5 Reasons Caspar David Friedrich’s Art Still Inspires Today

Remember that feeling when you’re standing on the edge of something vast, sea, cliff, sky, and for a moment nothing else matters? That’s the world that Caspar David Friedrich often invites us into. Born in 1774 in northern Germany, Friedrich became one of the key figures of the German Romantic movement.

What he did differently was simple yet profound: he stopped treating landscapes as just backdrops and made them the main subject. Mountains, mist, sea, these were not just places, they were experiences. His paintings were slower than many modern works, built around silence, reflection, and feeling rather than flashy effects. That slow approach is part of why his art still resonates today, when everything else moves fast, his landscapes stop you.

Today, artists and viewers alike return to Friedrich’s work for inspiration, not just technique. They look for the way he uses scale, atmosphere, and mood to speak about more than what you see. They look for what you feel.

In this article, we’ll explore five reasons Friedrich’s art still inspires today, and how, as an artist, you can pull those lessons into your own work so your landscapes don’t just show scenery, they invite presence.

Bohemian Landscape

Friedrich’s mountains and distant ridges in this piece have a quiet way of making you pause. It’s not just a landscape, it’s a gentle invitation to slow down and notice subtle details. When you’re creating your own landscapes, think about how you can make viewers linger instead of just glance. That little pause is where impact happens.

He layers foreground, middle ground, and background with careful attention, guiding the eye through the scene naturally. Try using soft transitions in your work; they give depth and make even a small painting feel expansive. Even if you don’t have sweeping mountains, layering elements can give a sense of scale.

Notice the muted colors and soft light here. They aren’t flashy, but they create mood. You can experiment with tone in your own work, sometimes using a subtle palette can communicate more than bold colors ever could. It makes the viewer engage emotionally rather than just visually.

The composition balances drama with calm. The peaks suggest grandeur, but there’s no chaos. You can replicate that balance in your own pieces by thinking about where the viewer’s eye lands first, where it travels next, and what emotion you want to leave them with.

Finally, there’s an understated narrative in this quiet landscape. Mountains rising, valleys receding, there’s a sense of journey even without people. In your work, think about story: what does your landscape say about passage, change, or reflection? A strong narrative element makes your art linger in memory.

Winter Landscape

This winter scene is deceptively simple, yet it carries an emotional weight. Friedrich uses snow, bare trees, and soft skies to evoke solitude and quiet reflection. When painting, think about how you can use minimal elements to convey a feeling, sometimes less truly is more.

The textures in this painting pull you in. The rough bark, the crisp snow, the distant shadows, everything invites touch in the mind of the viewer. In your own landscapes, experiment with tactile contrasts. It adds richness even in flat mediums like watercolor or digital.

Color here is restrained, almost monochrome, but it’s full of subtle shifts. It teaches that emotion doesn’t need bold hues. You can create depth and mood with nuanced tones, slight gradients, or tiny pops of accent color that catch the eye.

Compositionally, the horizon and tree placement are deliberate. They guide the eye naturally while leaving room for contemplation. Think about where your viewer will “stand” in the scene and how elements lead them on a journey through your painting.

Finally, the atmosphere is part of the narrative. Mist, shadow, and light create a story of space and season. When creating landscapes, consider weather and time of day as key players. They can dramatically affect the mood, and sometimes a slight hint of fog or a glow of morning light can make a scene unforgettable.

Riesengebirge Landscape with Rising Fog

In this work, the fog rolls over hills and valleys and you almost feel the moisture in the air. The scene isn’t static, it breathes. By painting rising mist over rugged terrain, Friedrich teaches that atmosphere can carry mood as much as form. As you work, try creating a piece where atmosphere is your subject. Let mist, light, and texture do the storytelling.

Notice how the land recedes into layers, closer ridge, mid‑valley, distant peaks. That layering builds depth and invites the viewer in. In your own landscapes think: how many layers can I see? How can I draw the viewer’s eye from front to back without distraction?

The muted yet varied palette keeps the scene unified and contemplative. You don’t need bold contrast to make impact. Try limiting your palette just slightly, and watch how subtle shifts create cohesion.

And then there’s scale: this land feels vast, but there’s no human figure to tell you how big it is. Let nature itself define the scale. When you forgo obvious human markers, you give space for viewer projection, and that’s powerful.

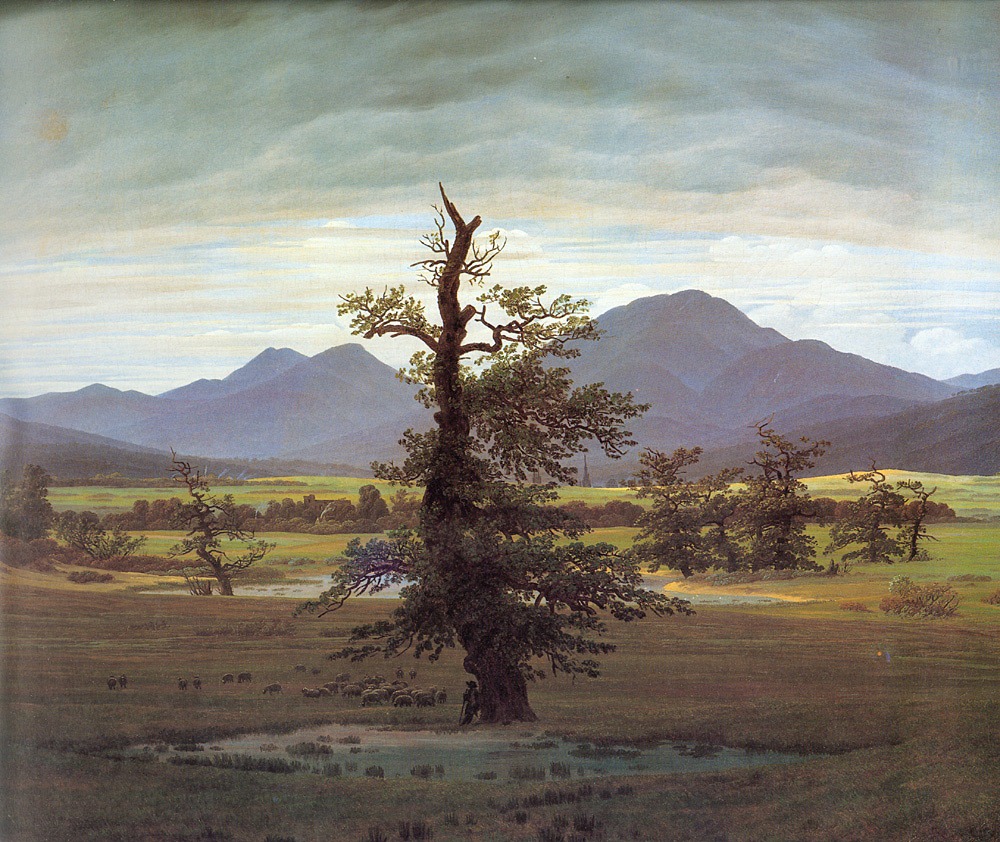

Landscape with Solitary Tree

There’s something quietly dramatic in a single tree standing alone in a field or landscape, and that’s exactly what Friedrich uses here. That solitary tree becomes the “voice” of the painting. In your own work, pick one focal element and let it carry the emotion. Surround it with space.

The landscape around it isn’t empty, it supports the tree but doesn’t compete. That balance matters. Think of your scene: what supports the subject vs. what competes for attention? Aim for harmony.

Observe the horizon and the light: how the background mountains hint at distance, how the foreground tree catches more detail. Your composition benefits when foreground, mid‑ground and background have distinct roles.

And mood: this scene feels calm, reflective, introspective. Not every landscape has to shout. Sometimes the quiet ones linger longest. Try creating one where your viewer might lean in instead of glancing away.

Northern Landscape, Spring

Here, Friedrich blends the edges of winter and spring, the land still holds cold hues, but there’s a hint of life waiting to emerge. That tension, between dormancy and growth, is rich territory. For your work, try a transitional scene: season‑change, light change, mood change.

See how the sky is heavy but the foreground holds gentle movement. Landscapes often tell stories of change even when nothing is “happening.” Ask: what is about to happen? What story does the landscape hold?

The palette stays tight but expressive: cooled tones, soft warm hints. You don’t need many colors to convey emergence. In your practice, test minimal palettes around transition moments, those can carry emotional weight.

Finally, notice how space ties everything together. The land opens; there are no strict boundaries. Viewers feel invited into possibility, not just observation. When you paint, think: am I inviting the viewer in, or presenting a scene to look at?