If You Believe Mistakes Ruin Art, Watch What Taylor Katzman Did After Punching Through Her Canvas

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve learned something important about exhibitions: the artists who shake you aren’t always the ones with the longest CVs or the most prestigious training. Sometimes they’re the ones who had to build their entire practice from scratch, without blueprints, without permission, without anyone telling them they were doing it right.

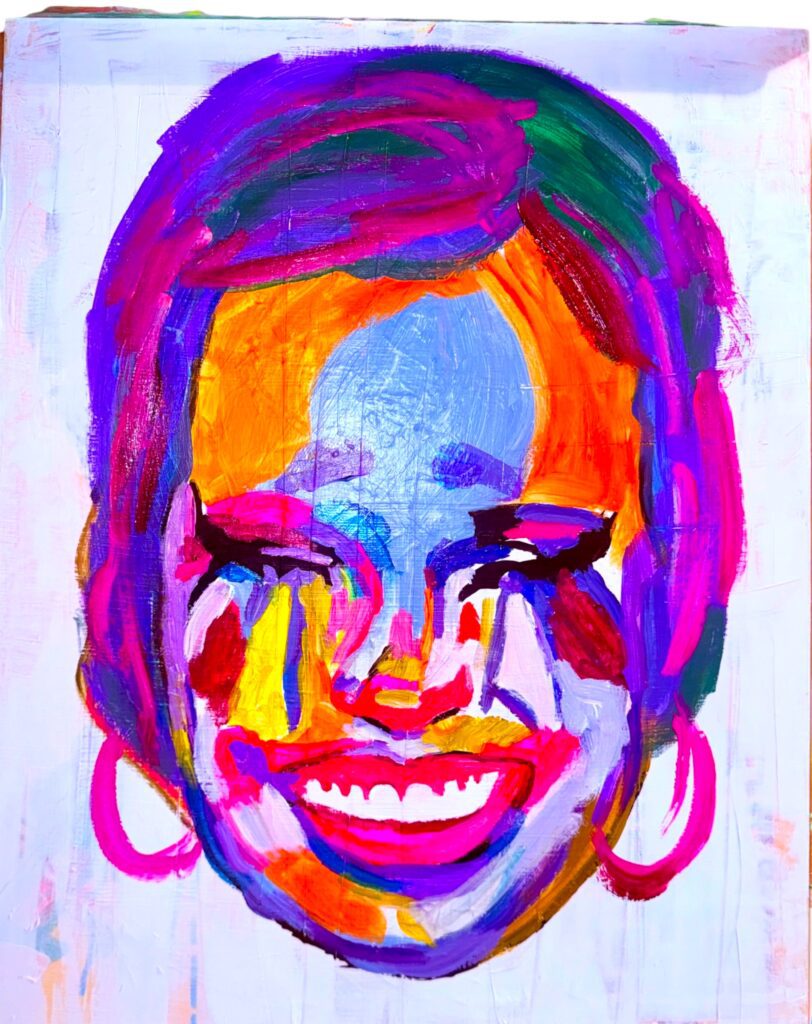

For our virtual exhibition Faces, we wanted to see how artists would approach the human face identity, expression, the visible and invisible parts of who we are. The submissions came in from everywhere. Some were technically stunning. Some were conceptually bold. And then there was Taylor Katzman’s work, which didn’t just show us faces it showed us what lies beneath them.

We selected Taylor not because her work was polished or safe, but because it was honest in a way that most artists spend years learning to fake. Her paintings carry emotional weight that doesn’t announce itself it just sits there, undeniable, waiting for you to feel it.

Taylor wasn’t formally trained in visual art. She came from ballet a discipline where technique isn’t optional, it’s survival. Where you learn structure to avoid injury, where rigidity can break you. When she transitioned into painting without formal training, there was no prescribed path, no rulebook she felt obligated to follow. And that freedom made her braver. Less boxed in. More willing to push, fail, repaint, and push again. Her personal style developed through instinct and repetition, not imitation.

Her work explores the complex layers of human emotion through faces and figures. It started with doodles drawings in the margins of notebooks meant for something else. Those early marks weren’t about aesthetics. They were about release, about responding to emotion before she had language for it. The face became a container for everything she didn’t know how to articulate yet grief, confusion, tenderness, anger, longing. That instinct never left.

She works with bold acrylics, strong contrast, expressive figures. Each piece has its own lifetime, born, lived, experimented with, refined. Some paintings live fast and loud. Others take their time. Some go through more than one life she’ll “finish” a piece, live with it, then take it apart to rebuild it into something else entirely. Intensity and restraint reveal themselves through the process. She follows what the painting asks for rather than imposing mood onto it.

There’s emotional territory she returns to again and again: reconciling guilt and forgiveness into a single, redemption-based whole. Guilt comes first immediate, unsettled, incomplete. That guilt motivates her work. Painting becomes her way of expressing discomfort and trying to make sense of it. Forgiveness enters later, through the process itself. As the painting develops, it teaches her something in return. Through that exchange, forgiveness slowly takes shape. Her work exists in that delayed reckoning—where guilt has settled in the body and forgiveness is being earned through reflection.

Acrylic lets her work at the speed of emotion. She can get something down the moment it shows up, before overthinking it. It’s bold and unforgiving, she can layer, destroy, refine, rebuild without worrying about dry time. Once it’s dry, it’s done. That pressure keeps the work honest and forces her to trust her gut instead of perfecting the life out of it.

Now, let’s hear from Taylor herself about giving form to what goes unspoken, about trusting emotional instinct without formal permission, and why sometimes the best thing you can do for a painting is punch straight through it.

Q1. Can you share your background and how becoming self-taught shaped the way you approach painting and visual communication, especially compared with formal training?

I’ve always thought of skill as something that grows best when it’s built on necessity rather than permission. I was formally trained in ballet, where technique isn’t optional—it’s survival. You learn structure to avoid injury. You learn discipline so your body doesn’t break. That experience taught me that fundamentals matter, but it also showed me the cost of rigidity. When I transitioned into painting without formal art training, there was no prescribed path, no rulebook I felt obligated to follow. There was no “injury” to avoid—only risk to take. That freedom made me braver. Less boxed in. More willing to push, fail, repaint, and push again. Over time, my personal style developed not through imitation, but through instinct and repetition. Being self-taught didn’t limit my visual language—it expanded it. It allowed my work to evolve organically, shaped by experience rather than expectation.

Q2. You describe your work as a way of exploring the “complex layers of human emotion” through faces and figures. How did the desire to communicate emotional nuance become central to your practice?

It goes back to why I started making art in the first place. Before paintings, there were doodles—drawings in the margins of notebooks that were technically meant for something else entirely. Those early marks weren’t about aesthetics or outcome; they were about release. I was always responding to emotion before I had language for it. Expression came first. The face became a container for everything I didn’t know how to articulate yet—grief, confusion, tenderness, anger, longing. Over time, that instinct never left. My work is still rooted in the same impulse: to shed what was once felt but never fully processed. Faces and figures became my way of holding those moments long enough to understand them.

Q3. Your pieces are marked by bold acrylics, strong contrast, and expressive figures. How do you decide when a composition needs intensity, and when it needs quietness or restraint?

I don’t decide in a traditional sense. I treat each piece like it has its own lifetime. It’s born, it lives, it experiments, it refines itself. Some paintings live fast and loud. Others take their time. Some even go through more than one life—I’ll “finish” a piece, live with it, and later take it apart to rebuild it into something else entirely. Intensity and restraint reveal themselves through the process. I follow what the painting asks for rather than imposing a mood onto it. Occasionally, a work feels complete and years later demands rebirth. I’ve learned to trust that cycle. The work knows when it’s done—temporarily or otherwise.

Q4. When creating work that’s deeply expressive, do you find yourself responding to your own emotional landscape, or stepping outside it to observe and translate?

Every piece holds a fragment of me, whether directly or indirectly. Sometimes I’m working through my own emotional experience. Other times, I’m observing someone else’s—empathizing, translating, holding space for it from a slight distance. I’m often moving between those two positions: participant and witness. Even when the emotion isn’t mine, the act of empathizing makes it personal. That third-person perspective allows me to tell stories that aren’t confined to autobiography but still feel intimate and honest.

Q5. Working outside formal conventions allows for experimentation. Can you describe a moment when experimentation led you somewhere unplanned but essential in a piece?

One of the most defining moments I’ve had while working didn’t come from curiosity so much as frustration. I was deep into a portrait that simply wasn’t working—no matter how much I adjusted it, it refused to resolve. In a moment of pure rage, I punched the canvas. It tore straight through. What could have been the end of the piece became its turning point. Instead of discarding it, I layered another canvas beneath the damaged one and rebuilt the painting around the rupture. The hole stopped being an accident and started reading as intentional—almost necessary. It introduced a physical vulnerability that mirrored the emotional tension I’d been trying to force onto the surface all along. That moment reshaped how I think about experimentation. Sometimes it isn’t gentle or planned. Sometimes it’s reactive, emotional, and a little destructive. But when I allow those moments to exist rather than correcting them immediately, the work becomes more honest. The damage told the truth faster than my control ever could.

Q6. Art can confront fear, uncertainty, empathy, or hope. Are there emotional territories you find yourself returning to again and again, even when the imagery changes?

I return again and again to a place where I find myself reconciling guilt and forgiveness into a single, redemption-based whole. These emotions exist in a cause-and-effect relationship—one inevitably following the other—but they rarely arrive at the same time. Guilt comes first. It’s immediate, unsettled, and incomplete. That initial guilt is what motivates my work. It’s the moment where I don’t yet feel whole about a situation, where something unresolved demands to be examined. Painting becomes my way of expressing that discomfort and trying to make sense of it. The work begins as an attempt to understand, not to resolve. Forgiveness enters later, through the process itself. As the painting develops, it begins to teach me something in return—about the moment, about myself, about what was missing. Through that exchange, forgiveness slowly takes shape, and I’m able to refine the work within a redemption-based mindset. That’s where my work lives. I make art after the fact, in hindsight, when redemption can no longer be negotiated in real time. The figures I paint exist in that delayed reckoning—where guilt has already settled in the body, and forgiveness is being earned through reflection. Painting becomes the space where that emotional circuit can finally close. Through the work, I’m able to return to moments that are otherwise inaccessible and offer something they didn’t receive when they needed it most: A VOICE! Not just any old voice, but a voice of wisdom rather than a voice of impulsive emotions. A voice that withstands time, a voice I’m proud to call my own. A voice that otherwise couldn’t be heard. In that sense, the act of making becomes an act of redemption itself—not just carrying guilt forward, but transforming it into forgiveness and completing the full circle.

Q7. You aim to forge a deep connection between viewer and subject. What do you hope someone feels when they first encounter one of your portraits?

I’m not interested in controlling the viewer or telling them what to feel. I don’t want to sway someone toward a specific interpretation or emotional conclusion. What matters to me is that the work holds their attention long enough to invite a personal response. If I’ve done my job, the viewer pauses. Their gaze lingers. Something in the figure feels familiar or unsettling enough that it pulls them inward. I want them to feel touched—not instructed. Whatever emotion surfaces for them is valid. The connection isn’t about transmitting my feelings onto the viewer; it’s about creating a space where their own emotions can rise to the surface.

Q8. Acrylic paint offers both intensity and fluidity. What does this medium allow you to express that others might not and what are its limits for you as an artist?

Acrylic lets me work at the speed of emotion. I can get something down the moment it shows up, before I overthink it or water it down. That’s huge for me, because what I’m painting lives in instinct—the stuff you feel before you can explain it. It’s bold and unforgiving, which means I can layer, destroy, refine, and rebuild without worrying about dry time or losing the energy of the moment. I love that acrylic doesn’t ask me to slow down or be polite. It also forces commitment. I don’t get to hover in self-doubt or dip my toes in first—I have to jump. Once it’s dry, it’s done. That pressure works for me. It keeps the work honest and forces me to trust my gut instead of trying to perfect the life out of it.

Q9. Looking back at where your work started and where it is now, what do you see as the thread that has remained most central to your practice?

The central thread in my work has always been the same: giving form to what goes unspoken. From the beginning, I’ve been focused on emotional translation—especially what shows up in facial expressions, body language, and silence rather than words. While my confidence, scale, and technical control have grown, the impulse hasn’t changed. I’m still drawn to moments that feel too private, fleeting, or uncomfortable to say out loud. What’s changed is that I no longer look for permission. The work has become more decisive, more visible, and more self-assured—but at its core, it’s always been about making internal states tangible and letting viewers recognize themselves without being told what to feel.

Q10. What advice would you give to artists who are learning to trust their emotional instincts, especially when working outside formal training or academic structures?

Trust what keeps showing up. If it matters, you’ll keep coming back to it. Don’t wait to feel ready. Make the work. Mess it up. Do it again. Pay attention to what you make when no one’s watching—that’s where your voice lives. You don’t need to explain every choice. If it feels necessary, it probably is. Technique can be learned. Instinct just needs use. The goal isn’t to do it “right.” The goal is to sound like yourself.

Talking with Taylor, I realized something I hadn’t put into words before: sometimes you have to break something to finally see what it was trying to become.

She punched through her canvas. Most people would’ve thrown it away. She didn’t. She looked at that tear and understood it was more honest than anything she’d been trying to paint. So she kept it. Built around it. Let the damage stay visible. That moment changed how she thinks about making art that mistakes aren’t failures, they’re the painting finally speaking louder than your control.

What stayed with me most is the emotional ground she works from. She paints the space between guilt and forgiveness that uncomfortable time when you can’t undo what happened but you’re trying to understand it. Her work doesn’t resolve that tension. It just holds it. Honestly. Without apology. And in doing that, it creates space for viewers to recognize their own unfinished business, their own delayed reckonings. That’s not abstract philosophy. That’s lived experience turned into something you can see and feel.

She came from ballet, where discipline keeps you from getting hurt. Then she moved to painting, where that same rigidity can kill what you’re trying to say. She kept the work ethic but dropped the rulebook. That’s the balance most artists never find structure without suffocation, freedom without losing your foundation. And her choice of acrylic reinforces this it dries fast, forces commitment, won’t let you hover in doubt. She works at the speed of emotion, capturing what surfaces before overthinking can flatten it.

There’s also something powerful in how she refuses to dictate meaning. She doesn’t tell you what to feel. She creates faces that work as containers you bring your own guilt, your own need for forgiveness, your own unspoken states. That generosity, that trust in the viewer, is what makes the connection real.

What Taylor taught me: being self-taught isn’t about what you’re missing. It’s about building from instinct instead of waiting for permission. Her work exists because she trusted what kept showing up, even when it was messy, even when it scared her. And sometimes the bravest thing you can do is let the rupture stay visible because that’s where the truth lives.

Follow Taylor from the links below to see work that doesn’t hide its scars where damage becomes honesty, where guilt and forgiveness coexist without resolution, and where the only thing that matters is having the courage to keep building even after everything tears.