Using Her Body as Material Was Never A Decision, It Was Simply The Most Honest Way To Work I Helena Barbagelata

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve spent years creating spaces where women artists can explore themes without being told what those themes should mean. Each exhibition is an invitation not a prescription. We choose a word, open submissions, and wait to see what artists bring.

For our Birds exhibition, we expected flight. Migration patterns traced in paint, wings catching light, freedom rendered in feathers and sky. We thought we knew what birds meant escape, lightness, the dream of leaving everything behind and rising.

And the submissions that came in were stunning. Hundreds of interpretations, each one bringing something beautiful, something honest. We selected many amazing artists whose work explored birds in ways that moved us, challenged us, made us see the theme from angles we hadn’t considered.

But then there was Helena Barbagelata. And her work didn’t just give us a new angle it made us realize we’d been thinking about birds too small the entire time. Her work didn’t show us birds. It showed us what it feels like to become one. And suddenly everything we thought we understood about the theme cracked open in ways we weren’t prepared for.

We selected Helena because her work does something most artists avoid it refuses to give you answers. She doesn’t explain, doesn’t decode, doesn’t smooth out the contradictions. She just creates this space charged, uncomfortable, impossible to ignore and then walks away, leaving you alone with questions you didn’t know you were carrying.

Before we hear from Helena directly, here’s what you need to know about an artist whose entire practice exists in a space most people spend their lives trying to escape.

Helena comes from fashion. She’s been photographed since she was young since an age when bodies are still figuring themselves out, still negotiating what they’re allowed to want and who they belong to. And there’s something about growing up that way, about being turned into image before you’ve finished becoming yourself, that teaches you things most people never learn.

She’s also carrying multiple cultures that don’t sit quietly beside each other. Backgrounds that crash into each other, create friction, refuse to be neatly categorized. And instead of trying to resolve that tension or pick a side, she built her entire practice inside the collision.

She works with her own body, but not in the way you might think. Not as subject, not as performance, not as commentary. As material. As the most honest thing she has access to. And there’s something about that choice about using the one instrument you can never put down, the archive you carry in muscles and breath and the way you stand when you think no one’s watching those changes what’s possible.

Her life is perpetual in-between. Between countries, between cities, between fashion and fine art, between what’s real and what’s dreamlike. Most people find that destabilizing, exhausting. Helena built her home there. And her work reflects what happens when you stop trying to land somewhere solid and start working with flight as permanent condition.

There’s also something about how she works with eyes that you need to understand before you see her images. She grew up in cultures where eyes do the talking before mouths open. Where entire conversations happen in glances.

Where you learn to read emotion and intention and truth in the way someone looks at you, not what they say. And that fluency that ability to communicate through gaze before language arrives is something most of us never develop. For Helena, it’s baseline.

She’s also obsessed with physics in ways that sound abstract until you realize she’s talking about how bodies actually work. About energy, vibration, the material reality underneath what we call “self.” And what that does to her practice how it changes what she thinks art is for, what bodies can do, what images can hold is worth paying attention to.

Now, let’s hear from Helena herself about what happens when you stop trying to belong anywhere, about why the body knows things before the brain catches up, and why sometimes the most honest thing you can create is a space for questions that refuse to be answered.

Q1. Can you share your background and the experiences that first drew you to work with your own body and image as a central material in your art?

My earliest creative impulses were never confined to a single medium. I sang, danced, drew, wrote, painted, each one an attempt to articulate sensations that exceeded language. But over time I began to realise that my own body was the constant, the one instrument I always carried with me. Growing into the fashion world intensified this awareness. Being photographed, initially at an age when the body is still discovering itself, confronted me with the strange simultaneity of selfhood and image. I felt, in a way similar to artist Francesca Woodman, that my body was both mine and not mine, a space of vulnerability and invention. And like the Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin, whose work taught me that the body can think before the mind formulates thought, I realised that movement, posture, and gesture were forms of philosophy. Eventually, it became impossible not to use the body as material. It was never a decision; it was simply the most honest way to work.

Q2. A lot of your work centres on self-portraiture and performance using your body as subject rather than an external figure. What does the body allow you to express that other media might not?

Although self-portraiture isn’t the primary form my art takes, the body remains a conceptual presence. The body carries a kind of pre-linguistic knowledge. It accumulates memory in its muscles, its breath, its reflexes. I am engaging with this embodied archive, an archive shaped by travel, cultural multiplicity, diasporic threads, and the constant reframing that modeling imposes. My work is focused on atmosphere, narrative, and emotional resonance, I’m more interested in how the body—any body—can become a vessel for metaphor, dream, or cultural memory. In Jewish thought, the face is an ethical event: a site of encounter with the Other. In Italian art, from Caravaggio to contemporary figures like Vanessa Beecroft, the body becomes a simultaneously sacred and political surface. My own work sits between these lineages. The portrait is a threshold where inner narrative and external gaze collide. What the body offers is immediacy. It resists abstraction, not because it cannot be stylised, but because it insists on presence, breath, and irreducibility. Working with the body is a way of staying accountable to the emotional truth of the image.

Q3. Many of your works resist easy categorisation, they’re documentary, performative, introspective, and visually stylised all at once. How do you think about category or genre in your practice?

Genre, for me, is porous. I come from fashion, where aesthetics shift rapidly and hybridity is the norm, and from a multicultural background in which identities are layered rather than singular. Categories seem inadequate in relation to the complexity of lived experience. I often think about the Italian Arte Povera movement, Jannis Kounellis, Michelangelo Pistoletto, artists who refused the boundaries between everyday material and artistic material. Or Israeli artists like Michal Rovner, whose work dissolves distinctions between documentary and abstraction. Their practices remind me that form must remain permeable if it is to reflect contemporary life. My work inhabits the in-between because that is where I live: between cultures, between cities, between fashion and fine art, between the real and the dreamlike. The refusal of category is not a strategy but a recognition of reality.

Q4. How does your experience as a model affect the way you compose, frame, or think about the camera in your own work?

Modeling taught me two opposing truths: the camera can be a mechanism of objectification, and it can be a mechanism of revelation. Understanding both sides grants me agency when I step behind or in front of it. I learned early the choreography of angles, but also the choreography of vulnerability. I learned how a lens amplifies intention, how light can sculpt identity, how stillness can speak louder than movement. This dual understanding allows me to engage the camera almost as a partner rather than an instrument. Over time I began to understand the camera less as a device and more as a thinking partner, something that doesn’t just record but intervenes, questions, distills. Every frame becomes a negotiation between appearance and inner truth, between what is framed and what escapes the frame.

Q5. Contemporary visuals circulate so rapidly and widely online. How do you feel about the speed and breadth of digital visibility compared with the slower, more deliberate experience of encountering an artwork in person?

The digital realm is both intoxicating and disorienting. Its speed mirrors the velocity of contemporary life, images flicker, travel, replicate, but they risk becoming untethered from depth. An image that took days or months to conceive can vanish in seconds into an infinite scroll. Encountering an artwork in person, by contrast, reintroduces duration. It recalls what the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls contemplative time, a time in which perception unfolds rather than reacts. Physical experience restores a sensuality: texture, scale, silence. I don’t see the two experiences as oppositional. Rather, I treat digital visibility as a kind of atmospheric layer around the work, while the physical encounter is the site of its true gravity. One disperses; the other anchors.

Q6. Your imagery often plays with gaze, restraint, and eyes as windows into emotion. How do you think about the way viewers read your eyes or presence in an image?

The eyes are the locus where agency and vulnerability converge. Modeling heightened my awareness of how the gaze can be sculpted, how it can seduce, confront, shield, or summon. But in my artistic work, I try to unlearn that choreography and return to something older, something instinctive, something that belongs to the body before performance. In both Italian and Jewish cultures, the eyes carry meanings that exceed language. The eye is a passageway, a site where the soul is sensed and entered rather than seen, a place where interiority rises to the surface. There is also a lived, everyday dimension to this. I’ve often witnessed how foreigners are startled by the intensity of silent communication in my cultures, the way an entire conversation can unfold in glances: warning, affection, irony, worry, approval. They disclose intention well before words arrive, a subtle form of character discernment that reaches beneath speech and into the truth of a person. I grew up inside that system of unspoken fluency, where emotion is broadcast without words and where truth rarely hides for long. So when viewers meet the eyes in an image, they’re not decoding a message I crafted; they’re encountering the afterglow of an internal state, an honesty that escapes the performance. The gaze becomes a shared field, a space of co-authored meaning rather than controlled intention. I surrender to that encounter because it feels like home: a communication older than language.

Q7. How do moments of rest or time away from making influence your clarity or direction when you return to the studio or image-making?

Rest is not absence, it is fermentation. My travels, moving through cities and countries, taught me that stepping away is essential for perspective.

In periods of rest, the subconscious rearranges things. Ideas soften, dissolve, reconfigure. The desert is a place where essentiality emerges; I feel that creative pauses function similarly. When I return to making, the work often arrives more distilled, more attuned. Rest sharpens intuition. It frees the work from urgency and invites it back into mystery.

Q8. You’ve been profiled across art and lifestyle platforms alike. Do you feel there’s a difference in how audiences in art spaces and fashion/media spaces interpret your work?

Yes, and I embrace the differences. Fashion audiences tend to read the work through aesthetics, gesture, and identity performance. Art audiences often read it through conceptual frameworks, lineage, and intentionality. Both readings are valid yet incomplete. The border between fashion’s performativity and art’s introspection is permeable. My own background encourages audiences to move between these lenses. The multiplicity of interpretations reflects the multiplicity of my practice. In travel, I’ve exhibited films and engaged in projects with underprivileged communities in remote places, spaces where art operates without the scaffolding of theory or the hierarchies of a cosmopolitan art world. Their responses, immediate, emotional, instinctive, remind me of the universality of art. I cherish witnessing how people from radically different social backgrounds interpret the work, how they connect through feeling rather than discourse. If anything, I hope the coexistence of these diverse audiences destabilises expectations rather than reinforces them, allowing the work to breathe in multiple registers at once: intellectual, visceral, and human.

Q9. When you look at your own work, do you see it more as artmaking or self-exploration or something else entirely?

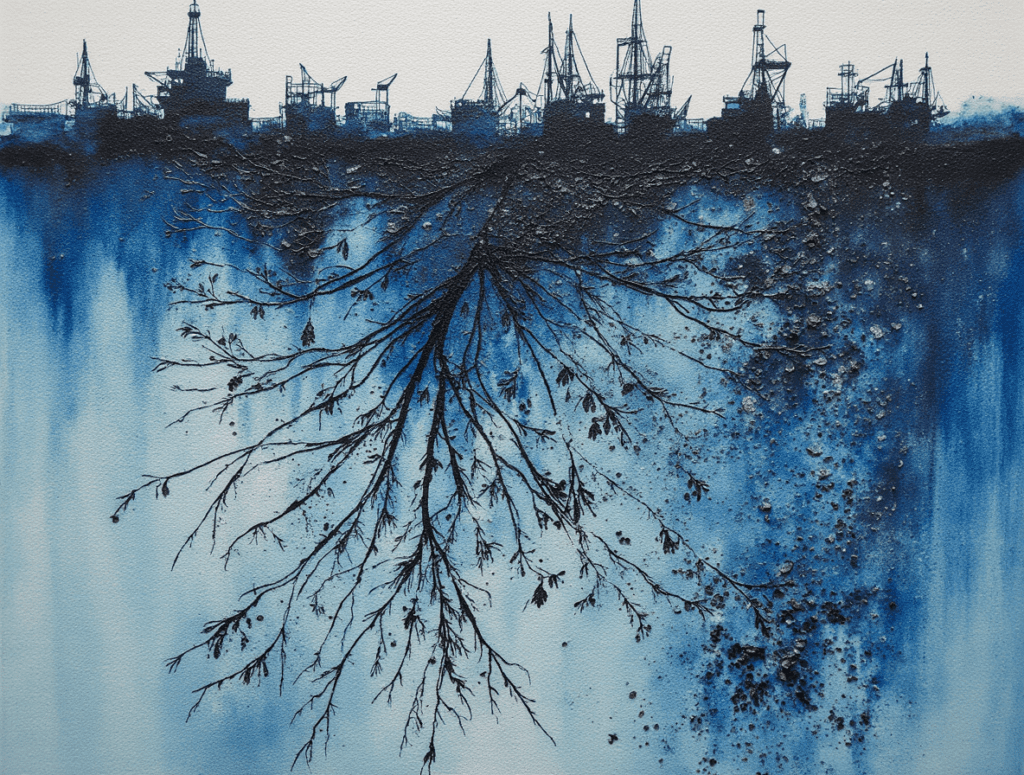

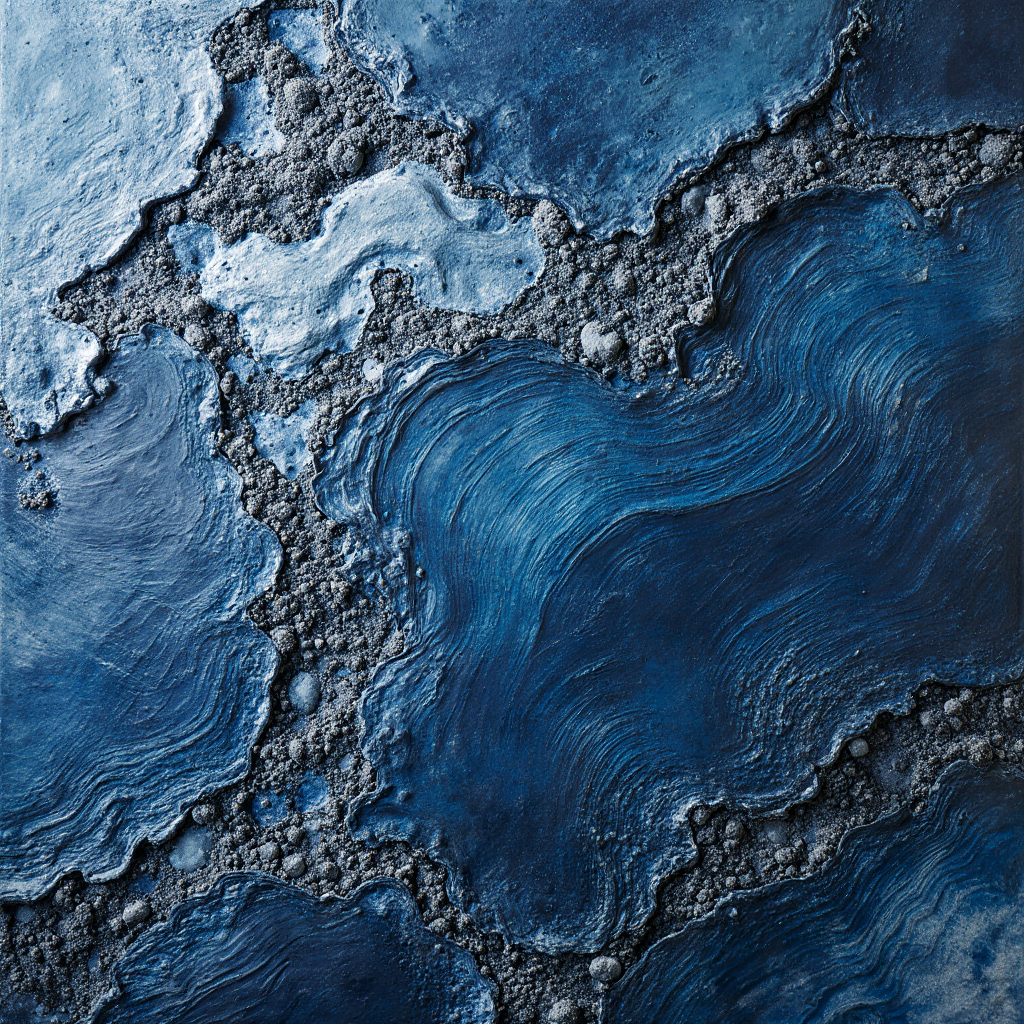

For me, artmaking begins as self-exploration, but it quickly transcends the boundaries of the individual. Introspection is only the entry point. Beyond it lies a vast field of myth, memory, and cultural inheritance, but also something more elemental: the fundamental matter of the universe that underlies everything we touch, feel, and imagine. I often think of creation in the language of physics. If, as string theory proposes, all existence is composed of vibrating filaments of energy—tiny resonances that structure reality—then making art becomes a way of entering into dialogue with that underlying pulse. Every stroke, every texture, every hue is simply a re-tuning of the same universal material, a small shift in the vibrations we all share. In that sense, the work is not about imposing form onto the world but about participating in its continual unfolding, rearranging matter and energy into new constellations of meaning. Art becomes a way of acknowledging that permeability: that the self is not a closed unit but an event, a momentary gathering of atoms, memories, and histories vibrating in time. This is why the work always exceeds me. It arises from me but also from the same fabric that composes oceans, cities, night skies, strangers, and distant stars. I often experience the process as a dialogue between the intimate and the universal—something like Buber’s I–Thou encounter, but on a cosmic scale. The artwork becomes a threshold where personal experience meets the deep logic of the universe, where the viewer’s resonance intertwines with my own. Meaning doesn’t reside in the image; it emerges in the energetic exchange between bodies, perceptions, and materials.

Q10. What advice would you give to artists who are exploring self, body, and image especially when those elements contain tension, ambiguity, or vulnerability?

Lean into the vulnerability, but anchor it with intention. The body is the most ancient artistic material; it carries cultural memory and personal history. When artists engage with it, they enter a long conversation, what matters is to honour the complexity of that lineage without allowing it to eclipse your own truth. Let ambiguity be generative. The unknown is fertile ground. Do not rush clarity. Allow meaning to emerge slowly. Protect the parts of yourself that are not ready to be revealed. Exposure must be chosen, not extracted. Treat the body as an interlocutor, not a tool. Listen to its resistances and impulses. Above all, remain honest. The viewer senses when the work is anchored in lived experience. Art that engages the body is always a risk. But risk is also a form of grace.

As we ended our conversation with Helena, and I can’t stop thinking about something most of us refuse to face: we’ve spent our entire lives trying to belong somewhere, and that might be the biggest lie we’ve ever told ourselves.

Here’s what kills me about her work she treats the body like it’s smarter than the brain. And she’s right. If you’ve ever walked into a room and felt wrong before you understood why or looked at someone and knew they were lying before they finished speaking, you already know what I’m talking about. Your body knew first. It always does. We just spend decades training ourselves to ignore it because listening would be inconvenient.

The thing about Helena that makes her work impossible to dismiss: she learned how to be both seen and seer simultaneously. She knows what it costs to be looked at before you’re ready, and she knows how to look back without forgetting that cost. That dual position vulnerable and in control at once is what most artists spend their entire careers trying to fake. She just lives there.

And here’s where it gets uncomfortable: she said something that should be tattooed on every artist trying to make “honest” work. Exposure must be chosen, not extracted.

We live in a culture that treats vulnerability like currency. The more you reveal, the more “authentic” you become. That’s complete bullshit. Not everything needs to be seen. Not every wound needs an audience. Forcing exposure before you’re ready whether that pressure comes from institutions, audiences, or your own desperate need to be understood that’s not honesty. That’s violence pretending to be art.

What her work actually proves: the artists who change how we see aren’t the ones with clear answers or fixed identities. They’re the ones who refuse to land. Who build entire practices in the space between worlds and say: what if this is where I’m supposed to be?

Because here’s the truth most of us avoid: the in-between isn’t where you get stuck waiting for real life to start. It’s where transformation becomes possible. It’s where your body knows things your brain hasn’t figured out yet. It’s where you stop performing coherence for people who need you to make sense.

Maybe that’s what birds actually mean in her work not freedom or escape, but proof that some things aren’t meant to land. That refusing to be grounded isn’t failure. Sometimes it’s the only honest option left.

What Helena taught me: we’ve been asking the wrong question our entire lives. It’s not “where do I belong?” It’s “what becomes possible when I stop trying to belong anywhere?” It’s not “when will I finally land?” It’s “what if I’m not supposed to?”

Follow Helena from the links below to see work that won’t give you answers but might finally give you permission to stop searching for ground you were never meant to stand on.