This is For Artists Who Feel Guilty for Not Working the Way They Were Taught I Paloma Ripollés

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve noticed something interesting about artists who have serious technical training behind them. Some of them spend their entire careers trying to honor what they learned by staying faithful to those methods, while others absorb everything their education gave them and then trust themselves enough to build something completely their own on top of that foundation.

For our Faces exhibition, we were looking for artists who understood that painting a face isn’t just about getting the features technically correct or making something that looks realistic. We wanted work that actually captured something harder to pin down, like what it feels like to be seen by another person, or how someone’s entire interior life can become visible through the way paint sits on canvas.

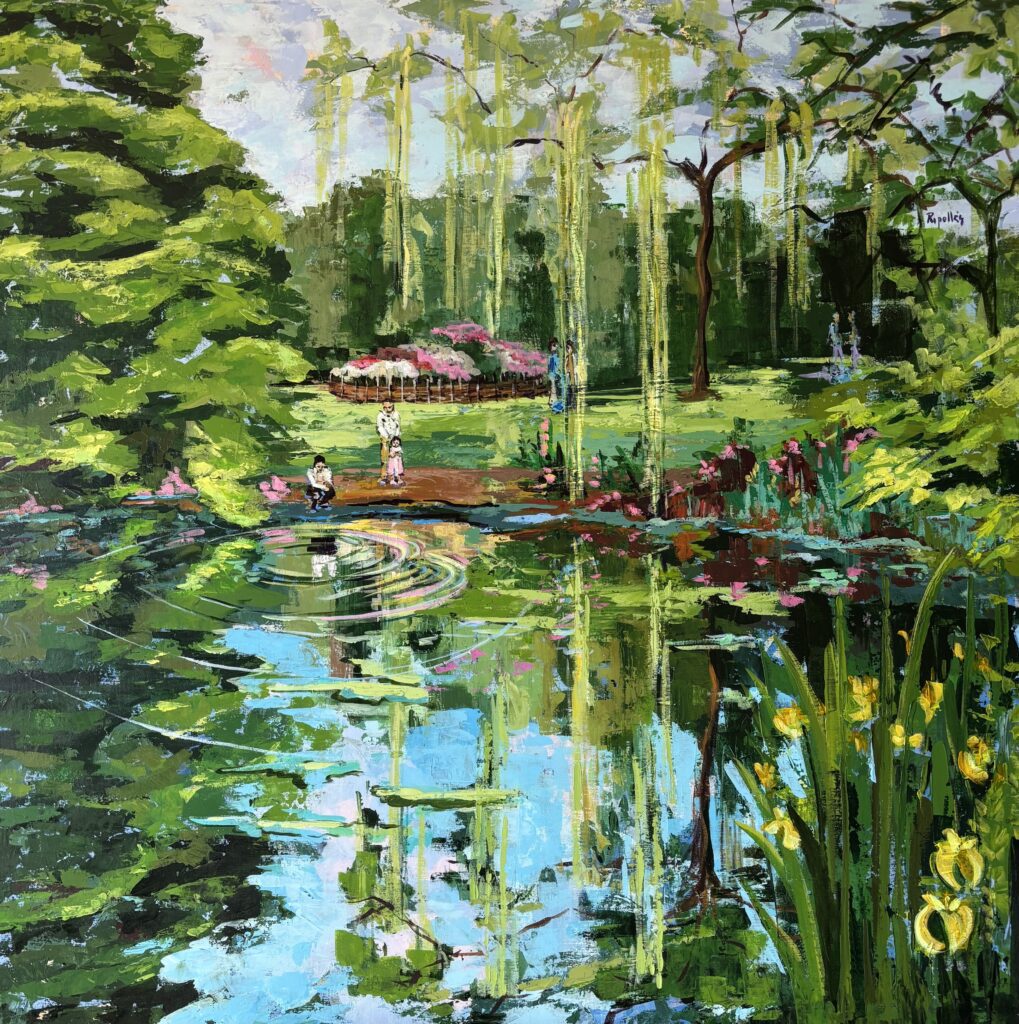

Paloma Ripollés’ work came into our submissions with a kind of confidence that you don’t see very often, the kind that only develops after decades of knowing exactly what you’re doing. Her surfaces vibrate with color in a way that makes you stop and actually look rather than just glancing and moving on.

We selected Paloma because her work shows what happens when technical mastery stops being about following rules and starts being about having enough skill to follow wherever your instincts lead you.

Before we hear from Paloma directly, here’s what struck us about her approach.

She’s someone who committed fully to this path early, not as a hobby or backup plan but as the central focus of her life. The training she received in Madrid was rigorous and comprehensive, the kind that builds foundations most artists spend years wishing they had. Then Florence, where she didn’t just study paintings in museums but actually lived surrounded by them, letting centuries of visual language seep in through daily exposure rather than formal study.

What’s immediately noticeable about her work is how she handles paint physically. There’s a directness to it, like the material is responding to thought without interference. The way she builds color relationships creates this optical effect where surfaces feel like they’re moving, breathing, refusing to sit still on the canvas. And there’s something intentional about how she approaches darkness in her paintings, building it from living colors rather than using anything that deadens the surface.

There’s also this quality of patience in her process that you can feel when you stand in front of the work. It’s like she’s not interested in forcing anything before it’s ready. She waits for the right relationship to form between what she’s seeing and what she’s feeling, and only then does the image find its way to canvas. That kind of patience is rare because most of us feel pressure to produce constantly rather than waiting for genuine readiness.

Her paintings don’t feel like documentation of what exists out there in the world. They feel like transformations, like everything has passed through her experience and memory and emotional state before becoming visible. The work carries traces of many places she’s lived and exhibited, but none of those influences dominate or compete with each other. They just coexist naturally, the way different experiences coexist in one person’s life without needing to resolve into a single story.

Now let’s hear from Paloma about what happens when you stop trying to paint the way you were taught and start painting what actually wants to emerge.

Q1. Can you share your background in fine arts and how your studies in Madrid and Florence shaped your approach to painting?

I knew from an early age that painting was my path. I studied Fine Arts at the Complutense University of Madrid, where five intense and joyful years immersed me in painting, anatomy, sculpture, photography, engraving, and restoration, shaping both my practice and my understanding of art history. Florence came next, officially to study art criticism, though in truth it was a way of living among masterpieces. Walking through the city, absorbing centuries of painting, left a lasting imprint on my work—especially in my use of color, which still echoes the Renaissance. My first solo exhibitions took place there, at Il Moro and Giardino dei Ciliegi, followed by Rome, and finally my return to Madrid, where I began my life as a professional artist.

Q2. Your signature technique involves using a spatula, complementary colours, and no black. What draws you to this method and how does it shape the expressive quality of your paintings?

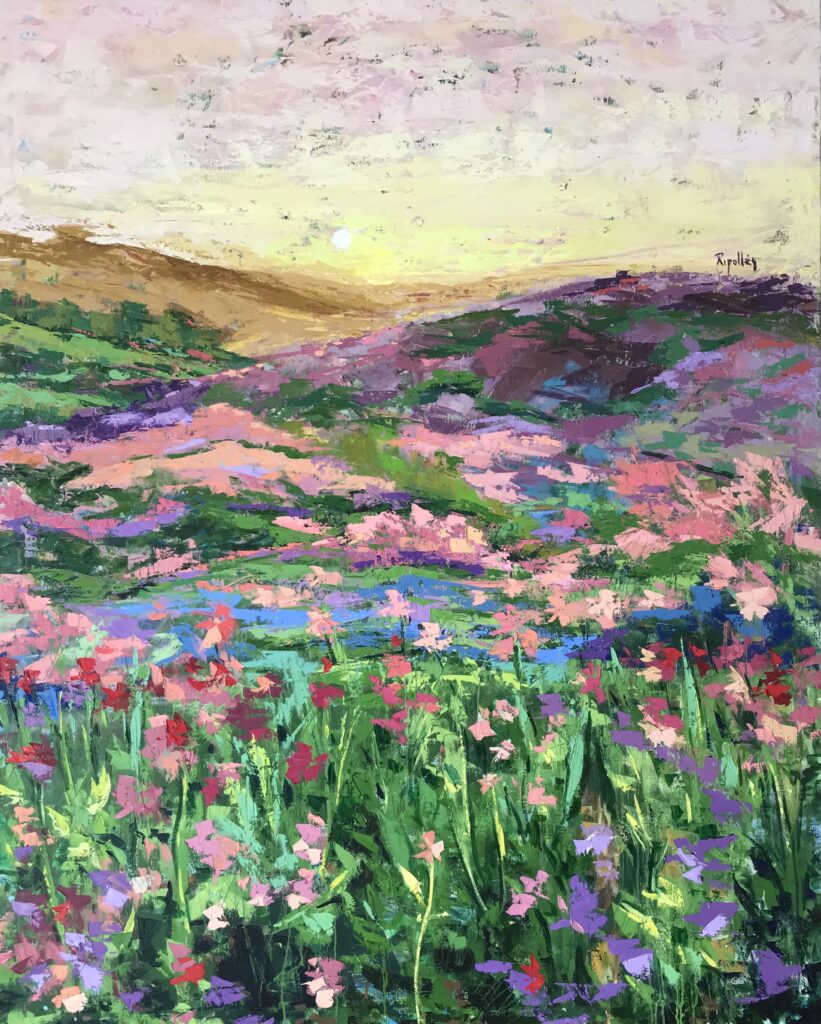

The spatula comes to me naturally—it feels like an extension of thought, a direct line from the mind, through the arm and hand, onto the canvas. It allows me to work instinctively, giving the paint body, texture, and movement. Through layering complementary colours, I aim to create a vibration on the retina, a visual energy that makes the surface breathe. I approach each painting as a complete organism, where every part contains the whole. While my work often begins in a space close to Impressionism, it can drift toward Expressionism or even Fauvism, depending on the emotional intensity of the moment. As for black, I never use it in its pure form—because pure black does not exist. Instead, I build my darks from mixtures of color, creating bluish, greenish, or reddish blacks that remain alive within the painting.

Q3. How do you decide on a colour palette for a new piece, and what role does colour play in conveying emotional or atmospheric tone?

I tend to work from a consistent colour palette, one that has become part of my visual language. For each new piece, I might introduce one or two new colours, often influenced by something I’ve recently seen—another exhibition, another painter, a moment that quietly stays with me. The choice also shifts depending on the medium; acrylic and oil demand different responses and rhythms. Colour, for me, is inseparable from emotion and atmosphere. I may visit a place many times and feel nothing, and then one day—suddenly—I’m in the right state of mind and I see it. In that moment, the image translates itself into my own language of colour, and I understand how it wants to exist on the canvas.

Q4. Nature, myth and imaginative visions appear frequently in your work. How do you navigate between external reference and inner imagery?

I don’t copy what I see; I make it mine. What comes from the outside is first absorbed, then interiorized and transformed within me before it reaches the canvas. The image passes through emotion, memory, and imagination, and only then does my arm translate what I see inwardly. The process is cyclical: something moves me, it enters, it transforms, and it comes back out in my own language. Everything depends on how I am feeling in that moment—because feeling is what ultimately shapes the image.

Q5. Your floral pieces such as Girasoles juxtapose delicate subject matter with vibrant colour fields. How do you see symbolism and sensation working together here?

Floral works are a part of my practice that I deeply enjoy because they offer a great sense of freedom. They allow me to play with layers and colour in a more abstract attitude, without losing the emotional presence of the subject.

For me, flowers are symbols of happiness and openness they bring oxygen into a space, both literally and emotionally.

A floral painting is like opening a window onto a garden: it invites light, air, and sensation into the room, where colour and feeling become inseparable.

Q6. Your work has been shown internationally, from Florence and Madrid to Miami and Belgium. How does exhibiting in different cultural contexts affect how you think about your work?

Living and exhibiting in different countries has deeply enriched my work. Each place has added something to my way of seeing—different cultures invite different perspectives and sensibilities. That said, the essence of my work always remains the same. What changes is the atmosphere that surrounds it. Landscapes from Latin America and the Caribbean live naturally in my paintings, just as urban experiences from cities like London and Madrid do. All these places coexist in my work, shaping it without ever diluting its core.

Q7. When beginning a new canvas, do you usually have a clear idea of composition, or does the work emerge more intuitively as you begin?

I usually begin with a clear idea of the composition, but the painting always finds its own way. Instinct and the unconscious inevitably surface in the process, reshaping what I first imagined. That is where the magic lies—in allowing the work to become something beyond intention, guided by intuition rather than control.

Q8. Viewers often describe your work as vibrant, uplifting, and evocative. How do you balance aesthetic appeal with deeper meaning or emotional complexity?

My intention is to provoke happiness and joy—to open spaces where the viewer can feel at ease and at peace. In difficult times like these, simply having something beautiful to contemplate becomes essential. Art invites pause. Even stopping for a few seconds in front of a painting can slow breathing, reduce stress, and lower cortisol levels—something science now confirms. Within that moment of calm, colour and form do more than please the eye: they create an emotional refuge, where beauty and meaning quietly coexist.

Q9. Many of your pieces evoke a sense of suspended time or atmosphere. When you aim to capture “light suspended,” what are you trying to communicate beyond the visual surface?

When I speak of “light suspended,” I’m trying to communicate a peaceful state of mind—a sense of stillness where time briefly slows down. It’s an invitation to stop, to remain present, and to feel your own emotions resonating with what I felt while painting. Beyond the surface, the work leaves space for imagination. I don’t want to dictate meaning; I want the viewer’s own inner images to emerge. That freedom of interpretation—where emotion, memory, and imagination meet—is what art truly is for me.

Q10. Looking back over decades of practice, what developments technical or conceptual feel most significant in your evolution as an artist?

As I live, my work continues to grow. Artistic development is inseparable from life itself. I keep learning, and I try to see as much work by other artists as possible—everything adds, everything leaves a trace. Technically and conceptually, I’ve become more open to experimentation, especially with new materials and processes. Over time, painting has become like handwriting: it evolves naturally, changing with experience, maturity, and time, while remaining unmistakably my own.

Q11. What advice would you give to emerging painters who want to develop a distinctive visual voice rooted in both technical mastery and personal expression?

A strong technical foundation is essential—it gives you freedom and confidence. From there, it’s important to understand that your way of working must be your own, not anyone else’s. When you trust that, the work begins to flow naturally. Keep going, stay honest with yourself, and allow your voice to emerge through practice and persistence.

Finishing our conversation with Paloma, something clicked for me that I think every artist needs to hear. Technical training isn’t your enemy. It’s your greatest gift. But only when you understand what it’s actually for.

Paloma has serious training. Five years of rigorous fine arts education. Time in Florence surrounded by centuries of masterworks. She knows anatomy, composition, color theory inside out. And here’s what makes her work so powerful: she uses all of it. Every single day. Just not the way anyone expected her to.

She works with a spatula instead of brushes because it connects her more directly to what she’s feeling. She builds her darks from living colours instead of dead black because she’s painting what she actually sees in nature, not what theory says should be there. She starts with clear compositional ideas and then follows wherever instinct leads because the magic happens when you let go of control. None of that dismisses her training. All of it builds on it.

Here’s what I love about her approach. She learned the rules so deeply that now she knows exactly when to trust them and when to trust herself more. That’s not rebellion. That’s mastery. Real mastery isn’t following instructions perfectly. It’s understanding principles so completely that you can make them serve your vision instead of limiting it.

She talked about how sometimes she visits a place multiple times and feels nothing. Then one day, she’s in the right emotional state and suddenly everything shifts. She sees it. Really sees it. And in that moment, the image translates itself into her language of color. She’s not forcing technique onto feeling. She’s letting feeling guide how she uses everything she knows.

That’s the difference between artists who stay stuck and artists who keep growing. The ones who grow don’t abandon their training. They absorb it so completely it becomes instinct. And then they’re free to follow wherever the work needs to go because they have the skills to support any direction.

If you’ve been trained well and now you’re working differently than you were taught, that’s not disrespecting your education. That’s honoring it. Your teachers gave you foundations so you could build something that matters to you, not so you could copy them forever.

Every rule you learned, every technique you practiced, every principle you absorbed, it’s all still there. You’re just using it to say something only you can say. And that’s exactly what training is supposed to enable.

Follow Paloma from the links below to see what decades of training look like when they become wings instead of weight, and proof that using your education to find your own voice isn’t betrayal. It’s the whole point.