Why Artists Today Are Willing to Be Misunderstood If It Means Being Real I Moreya

At Women in Arts Network, we believe in creating spaces where women artists can explore, experiment, and express without limitations. Each exhibition we host is built around a theme not to restrict, but to see what happens when hundreds of artists bring their unique perspectives to a single word.

Recently, we opened submissions for a virtual exhibition exploring the theme Faces. We wanted to see what artists would bring to something so universal yet so personal. How would they interpret the human face identity, expression, what we show and what we hide?

The submissions that came in were staggering. Portraits that felt like confessions. Abstracted features that revealed more than realism ever could. Faces as masks, as memory, as defiance, as vulnerability. Every piece offered a different truth.

And then Moreya’s work arrived, and it did something we weren’t prepared for. It didn’t just respond to the theme it ripped it open and showed us what lives underneath the surface we’re all trying so hard to maintain.

Her faces weren’t about beauty or recognition. They felt ancient, visceral, like they’d surfaced from the subconscious from places we’re taught not to look. They didn’t show you who someone pretends to be. They showed you what’s been suppressed, what’s hiding in the shadow, the parts we spend our lives trying to keep contained.

We selected Moreya because she understood what most artists avoid: that the most honest face isn’t the composed one. It’s the one that stops performing. The one that lets the raw, unfiltered truth come through, even when it’s terrifying to witness.

She was born in the Soviet Union, in a town drained of colour literally and emotionally. Even Moscow felt grey. Grim faces, empty shelves, a flatness that pressed down on everything. From childhood, she craved what she couldn’t find: intensity, emotion, life. So, she learned to invent it. She learned to transform the reality around her into something more alive, maybe even magical. That was her first rebellion not just against the physical environment, but against the emotional numbness it demanded. And she’s never stopped rebelling.

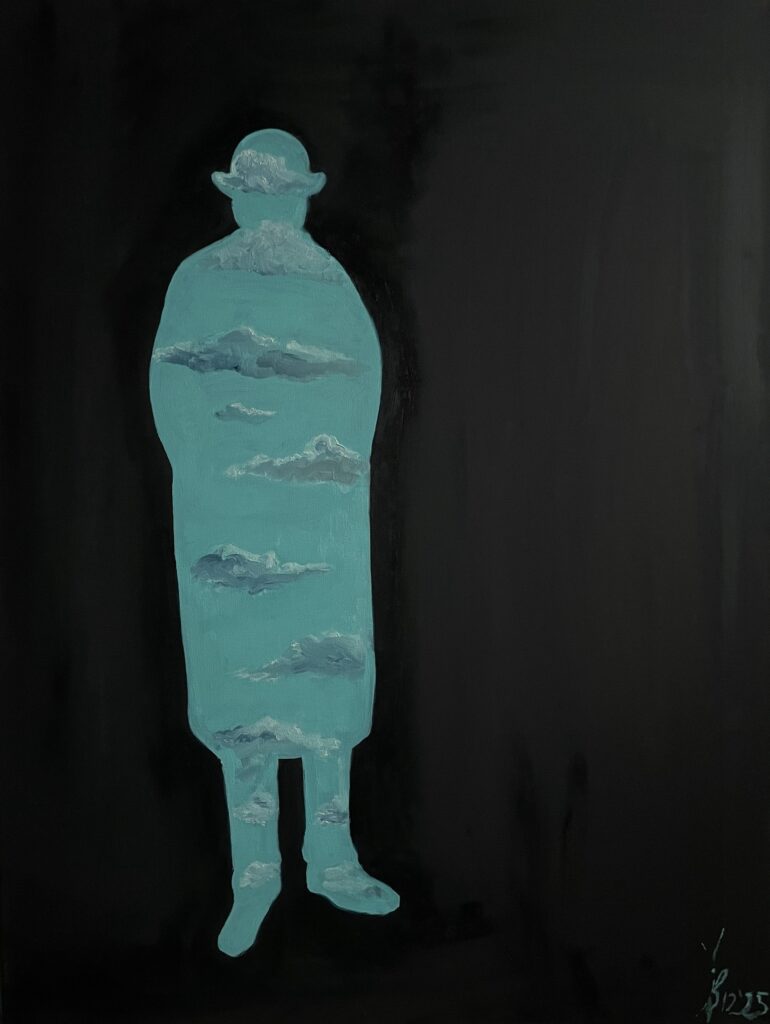

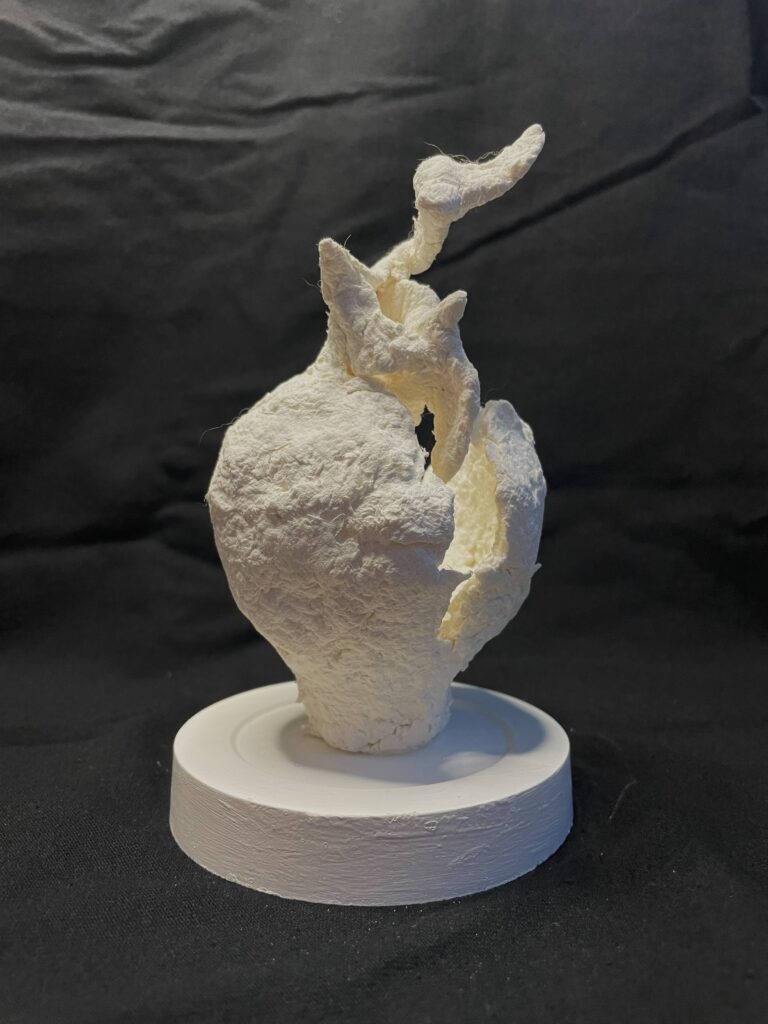

Her practice is built on refusal. Refusal to accept the world as it is without myth, without intensity, without transformation. She works in the space between figure and abstraction, where ancient art lives. Art that doesn’t rely on realism but speaks directly to the unconscious, bypassing logic, hitting you somewhere deeper.

Most of her ideas come in dreams or in that liminal space between waking and sleeping. Sometimes she can’t fall asleep until she sketches what’s surfaced. The images arrive complete immediate, almost fully formed. Her job isn’t to construct them. It’s to catch them before they dissolve. She rarely makes preparatory sketches. The image knows what it is. She just has to be fast enough to receive it.

Color, for her, isn’t decorative. It’s instinctive. When an idea arrives, it comes already tinted warm or cold, muted or luminous. She follows what the image is asking for. Color isn’t symbolism in her work—it’s emotional temperature.

A lot of her work centers on dark, complex, sovereign feminine energy. It’s tied to the women in her family her grandmothers, her mother, their pain, their silence. By reclaiming these darker aspects of femininity visually, she’s doing soul work. Freeing them. Freeing herself. She’s working with Carl Jung’s Personal Shadow: integrating the parts of femininity that were historically suppressed, silenced, feared.

In her work, the body isn’t fixed. When it becomes abstracted or obscured, it becomes a vessel for emotion, for memory, for states that can’t be verbalized. The body is where the subconscious becomes visible. It’s not a character. It’s presence. A field where transformation happens.

She doesn’t want polite reactions. She wants impact. If someone feels fear, desire, resistance that’s the point. It means the piece reached something usually left untouched. She’s not interested in comfort. She’s interested in what shifts inside you, even if it’s unsettling.

The core question running through everything she makes: how human and how authentic do we allow ourselves to be? Contemporary society is obsessed with comfort with avoiding anything that threatens emotional stability. But the things we try to avoid are often what make us feel alive. Her work keeps asking: what happens when we stop numbing ourselves? What surfaces when we let the raw, unfiltered states come through?

Now, let’s hear from Moreya herself about rebellion as practice, about following instinct over fear, and why darkness isn’t the enemy, but it is territory that holds what you’ve been looking for.

Q1. Can you share your background and the personal experiences that led you toward a practice rooted in emotional intensity, transformation, and inner states rather than representation alone?

I think it all started with being born in the Soviet Union. The town I grew up in was grey and dull, literally. Even Moscow, the so-called capital, felt monochrome dirty: grim citizens in badly made clothes, scanning shelves for something to feed themselves and their children. From the very beginning, I craved color and emotion things I couldn’t find in the landscape around me. So I had to invent them. I learned to transform the reality I saw into something more meaningful, more sensual, more alive. Maybe even magical. It was a rebellion — not just against the environment, but against the emotional flatness it imposed. And I’m still rebelling. My practice is rooted in that refusal: to accept the world as it is, without myth, without intensity, without metamorphosis, without philosophic depth.

Q2. Your work suggests a long visual and personal journey toward reconciling figure and abstraction. Was there a moment when you knew your art would live in that intersection rather than in a single style or language?

When I started painting, I simply wanted to express something inside me that I couldn’t yet name. What appeared on the surface never matched what I felt. At the beginning, I assumed it was just a matter of skill, so I focused on technique, trying to “fix” the gap between vision and result. But the more I worked, the more I realized that the answer wasn’t in precision of the brushstroke — it was in the ability to deliver a certain message. I became interested in generalization, in reducing forms to something essential, almost archetypal. Ancient art has always fascinated me for that reason. It’s incredibly expressive without relying on realism; it speaks directly to the unconscious, bypassing logic entirely. At some point I understood that this intersection — between the figure and abstraction, between the seen and the felt — is where my work naturally lives. It’s the only place where I can recreate the kind of impact ancient images have on me: immediate, visceral, and deeply internal.

Q3. Much of your imagery feels like it emerges from a subconscious or dream-state. How do you enter that psychological space while working?

It’s true — most of my ideas either come to me in dreams or in that liminal space between waking and sleeping. Sometimes I literally can’t fall asleep until I sketch whatever appears in my mind. Ideas are everywhere; it’s just that some people have fewer distracting thoughts and anxieties, so they catch those ideas more easily. I seem to be one of them. I don’t use any special methods to “enter” a psychological state. There’s no ritual, no deliberate shift of consciousness. Usually, finishing one work is enough for the next idea to arrive. It’s a continuous chain, almost an ecosystem of images feeding into one another. That’s also why I rarely make many preparatory sketches. If you follow the “proper” academic approach, you’re supposed to plan, refine, adjust. But in my case, the image usually comes as a whole — complete, immediate, almost fully formed. My task is simply to catch it before it dissolves. Frankly, I would appreciate to have some control under this part of my creativity, but it seems for me impossible at the moment

Q4. You use the word transgressive not as provocation, but as a necessity. What needed to be crossed, broken, or released for this work to exist?

For me, “transgressive” isn’t about shocking anyone, and for the most part, it’s not even about visible manifestations it’s about crossing the internal borders that keep the work from happening in the first place. Something had to be broken, yes: the set of limitations I inherited: cultural, emotional, even bodily. I had to break the idea that art must be polite, coherent, or visually “correct.” I had to release the pressure to be readable, to be approved, to be aligned with any school or expectation. And I had to cross the boundary between what I felt and what I allowed myself to show. That was the hardest part. Transgression, for me, is a form of liberation — from fear, from inherited narratives, from the need to justify intensity. Without crossing those internal thresholds, the work would remain a sketch, a hesitation, a compromise. It exists only because something in me was willing to step over the line and not look back.

Q5. Your use of colour often feels like a metaphor luminous, muted, or unexpectedly warm or cool. How do you decide when a colour should hold emotional weight versus when it should recede?

My use of color is almost entirely intuitive. I don’t “decide” in a rational sense whether a color should carry emotional weight or step back, it reveals itself in the process. Some colors insist on being present; others fade on their own. I simply follow that internal pull. Color, for me, isn’t a tool of symbolism or a calculated metaphor. It’s more like an emotional temperature that appears together with the image itself. When an idea comes to me, it usually arrives already tinted — warm, cold, muted, or luminous. My task is not to impose logic on it, but to stay sensitive enough to catch the tone it brings. Because of that, I rarely think in terms of foreground and background, or “important” versus “receding” colors. The emotional weight distributes itself naturally. If I try to control it too much, the work becomes stiff. When I trust the instinct, the palette finds its own balance.

Q6. Many of your works centre feminine energy that feels dark, complex, and sovereign. How important is it for you to reclaim these aspects visually?

This aspect is tied to the complicated and often contradictory history of the women in my family. I carry their stories — my grandmothers, my mother — and I feel the weight of the pain they lived through. Reclaiming these darker, more complex forms of feminine energy is, for me, a way of freeing their souls from that inherited suffering. And, of course, freeing myself as well. The archetype of the woman as a being who both gives life and can take it away — connected to the earthly world and the underworld at the same time — exists in every culture. It’s ancient, powerful, and often suppressed or sanitized because it is menacing. Visually reclaiming it is important because it allows me to restore that sovereignty, that depth, that duality. It’s not about idealizing femininity, but about acknowledging its full spectrum, including the parts that were historically silenced. It is about uniting with the Personal Shadow in the meaning of Сarl Gustav Jung

Q7. Do you see the body in your work as a symbol, a witness, or something else entirely especially when it’s abstracted or partially obscured?

I don’t see the body in my work as a single fixed entity. It’s something more fluid. When the figure becomes abstracted or partially obscured, it stops being “a body” in the literal sense and turns into a vessel for an inner state. Sometimes I feel myself like a fine tuned receiver of strange vibrations. It’s where emotion becomes form, where the subconscious becomes visible. Sometimes it carries memory; sometimes it carries tension; sometimes it’s simply the echo of an experience that can’t be verbalized. When I distort or fragment it, I’m not hiding it — I’m revealing the parts that are usually invisible. In other words, the body in my work is not a character or an illustration. It’s a presence. A container. A field of transformation. It holds whatever needs to surface, whether it’s tenderness, fear, desire, or something darker and unnamed.

Q8. Your work can provoke strong reactions. How do you feel when viewers project fear, desire, or resistance onto the images?

That is exactly what I hope for. I don’t create work to comfort people or to offer a neutral experience. If someone projects fear, desire, or resistance onto an image, it means the work has reached a place in them that isn’t usually touched. Those reactions tell me the piece is alive — that it’s doing something, shifting something, unsettling something. I’m not interested in polite viewing. I’m interested in impact. If the work provokes a strong emotional response, then it has fulfilled its purpose. I dream that my works will tangibly change the space around them. Υou know, sometimes it happens.

Q9. Across different pieces, there’s a consistent emotional temperature. What do you feel is the core question running through everything you make?

I think the core question running through all my work is about how human and how authentic we allow ourselves to be in everyday life. What touches us. What disturbs us. What pulls us out of balance. Contemporary society is obsessed with comfort — with insulating ourselves from anything that might threaten that comfort, emotionally or existentially. But the things we try to avoid are often the very things that make us alive. I can say that my work keeps circling around this tension: what happens to us when we stop numbing ourselves, when we let the raw, unfiltered states surface. What sets us free from boundaries of security and fears. In a way, I’m always asking: What remains of us when the protective layers fall away?

Q10. How do you imagine someone experiencing your work not just seeing it, but feeling it, moving around it, or sitting with it over time?

I imagine the experience of my work as something that unfolds rather than something that is “seen” in a single moment. The first encounter is usually visceral — a hit of emotion, tension, or unease. But if someone stays with the piece, moves around it, or returns to it later, the work starts revealing different layers. I don’t expect viewers to decode anything. I’m more interested in what happens inside them: how their own memories, fears, or desires begin to interact with the image. The work becomes a kind of mirror, but a distorted one it reflects not the surface, but whatever is already simmering underneath.

Q11. What advice would you give to artists who feel drawn to darker, more instinctive material but hesitate out of fear of being misunderstood?

I would say this: being misunderstood is inevitable, but being untrue to yourself is unbearable. If you feel drawn to darker, more instinctive material, that impulse is already a form of knowledge. It’s telling you where the real work is. People will always project their own fears and narratives onto what you make. You can’t control that, and you shouldn’t try. The only thing you can control is whether you stay loyal to the instinct that brought you to the work in the first place. Darkness isn’t the enemy. It’s a territory. And if you’re afraid to enter it, that usually means there’s something important waiting there. The misunderstanding will pass; the integrity of the work will remain. So my advice is simple: follow the instinct, not the fear. The right viewers will find you. The others were never your audience to begin with.

As our conversation drew to a close, Moreya left me with something I can’t shake: being untrue to yourself is unbearable, but being misunderstood is just part of the cost.

Most artists spend their careers trying to be understood, to be accepted, to make work that lands safely. Moreya does the opposite. She crosses internal borders most people won’t touch breaking inherited limitations, releasing the pressure to be polite or visually acceptable, showing what she feels without filter. That transgression isn’t about shocking anyone. It’s about making work that actually matters, even when it costs you comfort.

What struck me hardest is how she approaches darkness. She doesn’t avoid it or apologize for it. She enters it deliberately, knowing that if you’re afraid of a territory, there’s usually something important waiting there. Her work reclaims the suppressed aspects of feminine energy not the sanitized version, but the full spectrum. Life-giver and destroyer. Nurturer and terror. She’s doing Carl Jung’s Shadow work visually, freeing not just herself but the souls that came before her.

The core truth running through everything she said: contemporary society is obsessed with comfort, with avoiding anything that might disturb us. But the things we try hardest to avoid are often what make us feel most alive. Her work keeps asking what remains of us when all the protective layers fall away? What do we find when we stop numbing ourselves?

What I learned from Moreya: if you feel pulled toward darker, more instinctive material, that pull is already knowledge. It’s showing you where the real work is. People will project their fears onto what you make you can’t control that. The only thing you control is whether you stay loyal to the instinct that brought you there. The misunderstanding will pass. The integrity of the work remains.

Follow Moreya from the links below to see faces that refuse to perform that show you not who someone pretends to be, but what’s been hiding underneath all along, demanding to be seen.