What Happens When You Stop Painting What You Studied and Start Painting What You Are I Sara Jacob

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve learned that the most powerful work doesn’t try to make sense for you. It just exists refusing to simplify itself, refusing to choose one story when it’s carrying several.

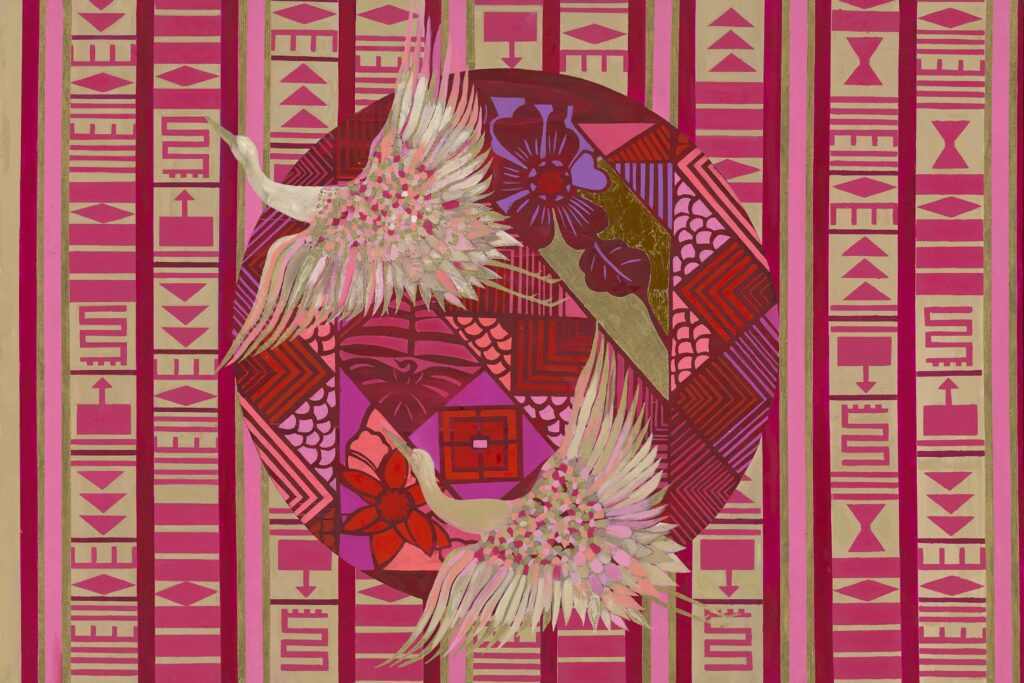

For our Birds exhibition, we expected migration rendered in wings and sky. What we didn’t expect was someone who would crack open what migration actually means not the physical crossing, but the impossibility of leaving anything behind when everything you’ve ever absorbed is still moving inside you.

While we were reviewing submissions, our eyes caught Sara Jacob’s work and we couldn’t figure out how to categorize it. Which turned out to be exactly the point.

Not because it showed us birds. But because looking at her paintings feels like overhearing a conversation in multiple languages where somehow, against all logic, everyone understands each other perfectly.

We selected Sara because her work does something most artists carefully avoid. She’s not painting from a place of having figured things out, of having a clear cultural identity she can present neatly. She’s painting from the middle of the storm where heritage is still colliding, still creating friction, and instead of trying to calm it down or organize it, she’s letting that collision be the entire point.

Sara is from everywhere and nowhere at once. She grew up moving between Berkshire, Nigeria, and the North of England. Not as a tourist passing through, but as someone who had to live in all those realities simultaneously. Imagine trying to form a sense of self when every culture you’re absorbing contradicts the others, when there’s no single story that holds everything together. Most people spend decades trying to resolve that, trying to become one unified thing. Sara looked at that impossible task and decided to paint from the chaos instead.

The way she uses fabric in her work is unusual. It appears in her paintings almost like a character, like it’s carrying information that paint alone can’t hold. Indigo dyed cloth woven through her compositions as if the fabric itself remembers things, holds stories, speaks in a language older than words. It’s not decorative. It feels necessary, like without it the whole painting would lose its ability to communicate something essential.

And then there’s this historical thread running through everything she makes. Connections between the Benin people and Japan that sound like myth until you start researching and realize they’re documented. Shared language roots, spiritual practices that mirror each other, craftsmanship techniques that evolved continents apart but somehow arrived at similar conclusions.

She’s not using this as background flavor. She’s building her entire practice on the question of what it means when cultures that never touched still echo each other across time and space.

The detail that stopped us completely is this. Sara paints with her grandmother’s actual oil paints. Her grandmother was part of the Lagos art scene, left these materials behind, and Sara still uses them. Not as homage, not symbolically.

Every painting she makes contains the literal substance her grandmother once held. Which means lineage isn’t abstract in her work. It’s physically present in every layer, every stroke. Inheritance as material reality rather than concept.

One of her pieces uses gold leaf to talk about migration and spiritual journeys. But the way she describes working with it suggests she’s not trying to make history decorative or pretty. She’s trying to make the past feel like it’s still unfolding, like migration isn’t something that happened once but something that keeps happening inside us, across generations, whether we’re moving geographically or not.

Now let’s hear from Sara about what it actually costs to create when you’re painting from multiple worlds that refuse to stay separate, and why the truest form of migration might be the one that never stops happening in your own body.

Q1. Can you share your background, where you grew up, how your British and Nigerian heritage shaped your early relationship with art, and when you first decided to become a multidisciplinary artist?

I first began to see myself as a multidisciplinary artist through my education. Studying Art A Level at Berkshire College of Art and Design in the late 1990s encouraged me to explore cultural narratives more deliberately. This continued through my fashion studies, where I combined Nigerian influences with Japanese kimono-style design, and later through my training in interior architecture. By 2012, as I began working across painting, fashion, and spatial design, it became clear that my practice could not be confined to a single discipline. Instead, I embraced a multidisciplinary approach, using different mediums to explore identity, culture, and space as interconnected forms of expression. I grew up between Berkshire, Nigeria, and the North of England, experiencing a mix of cultures, colours, and visual patterns that deeply shaped how I see the world. Art was always instinctive—drawing and painting allowed me to express beauty and emotion from a young age. My British and Nigerian heritage gave me a sense of contrast and layering, which later became central to my work. I realized I was a multidisciplinary artist during my studies in art, fashion, and interior architecture, embracing multiple mediums to explore identity, culture, and space.

Q2. The use of indigo-dyed cloth and fabric symbolism appears repeatedly in your work. How do you think about fabric not just as pattern but as language and cultural meaning?

For me, fabric is never just decorative it’s a language carrying memory, history, and identity. Indigo-dyed cloth, especially in West African traditions, conveys knowledge, spirituality, protection, and social status. Patterns, dyes, and making methods tell stories of place, lineage, and lived experience, and growing up between cultures made me particularly aware of this.

In my work, textiles act as carriers of cultural memory and as architectural elements, defining space, rhythm, and movement. Repeating indigo becomes a visual vocabulary to explore heritage, migration, and resilience.

Q3. You’ve incorporated narratives about ancient connections between the Benin people of Nigeria and Japan, could you explain how these historical threads inform a sense of shared human identity in your work?

The history of the Benin people is extraordinary—massive earthworks, advanced urban planning, a formidable military, and rich artistic traditions. Parallels with Japan, from shared names and greetings to reverence for sky gods and mastery in craftsmanship, highlight how distant cultures can converge in language, spirituality, and artistry. In my work, these connections aren’t coincidences; they illustrate a shared human capacity for creativity, exploration, and meaning making, challenging the idea that innovation is confined to certain regions. Narrative Implications – In my work, these threads are not just historical curiosities—they serve as a counter-narrative to the idea that advanced innovation was limited to certain regions. They invite us to see human ingenuity as widely distributed and to reconsider what “possible” means when we examine history through a lens that honours all civilizations equally. The beauty here is that these connections—linguistic, spiritual, artistic, even martial aren’t just coincidences; they suggest a deeper story about humanity’s shared capacity for creation, reverence, and exploration.

Q4. Your paintings often include highly detailed oil on canvas with integrated symbolic language; how do you balance intricate detail with conceptual depth in your creative process?

For me, detail and concept develop together. I start with ideas rooted in cultural memory, space, or symbolism, and the intricate oil layers become a way of thinking through them. Detail draws the viewer in, revealing deeper narratives over time, while areas of restraint give space for the concept to breathe. Every mark, pattern, or symbol is intentional, supporting the story without overwhelming it, so the surface’s richness and the work’s layered meaning coexist. Ultimately, the conceptual depth comes from intention and clarity of purpose. The detail supports the idea rather than overwhelming it. If a mark, pattern, or symbol doesn’t contribute to the narrative or emotional resonance of the piece, it doesn’t remain. The goal is for the viewer to experience both the tactile richness of the surface and the layered meaning beneath it, without one overpowering the other.

Q5. The influence of your grandmother, Nora Majekodunmi, and her legacy in Lagos art circles echoes through your work, how does this familial lineage continue to shape your artistic purpose?

My grandmother, Nora Majekodunmi, instilled a deep respect for creativity, cultural storytelling, and artistic excellence. Her legacy in Lagos art circles inspires me to explore heritage, identity, and cultural memory in my work, and reminds me that art can connect personal history with collective narratives. she also left me with her oil paints which i still use in all my works today.

Q6. Your paintings frequently explore identity through pattern and symbol; how do you hope viewers encounter and interpret these embedded visual languages?

I hope viewers encounter the patterns and symbols in my work intuitively first, before trying to interpret them intellectually. Pattern has a universal pull it draws the eye, creates rhythm, and invites the body into the work. That initial, almost sensory engagement is important to me, because it allows people to connect emotionally, regardless of their cultural background or prior knowledge. Ultimately, I want the work to function as a meeting point rather than a statement. The patterns and symbols are invitations into a shared space of reflection, where personal identity, cultural memory, and collective human experience intersect. If viewers leave feeling both grounded in their own perspective and open to another way of seeing, then the visual language has done its work.

Q7. Your 24k gold leaf piece Voyage Benin to Japan speaks to migration, history and spiritual connection, how do you approach bringing history to life visually rather than just conceptually?

With Voyage Benin to Japan, my goal is to make history felt rather than simply explained. I approach history as embodied—carried through materials, surfaces, and atmosphere—rather than purely intellectual. The 24k gold leaf is central: gold holds spiritual and symbolic resonance across cultures, evoking divinity, power, protection, and transcendence, and allows history to exist as light, reflection, and presence. Visually, I build layers and rhythms that suggest movement, passage, and migration without literal depiction. The surface becomes a map of memory and spiritual travel, while moments of restraint give space for ambiguity and interpretation. The viewer is invited to step into this space and experience history as living, relational, and constantly reinterpreted.

Q8. Your practice often merges storytelling, cultural memory, and visual invention, what do you hope people carry with them after seeing your work?

I hope people leave my work with a sense of connection—to their own histories, to other cultures, and to the shared human impulse to tell stories through making. My practice is about remembering and reimagining, holding cultural memory alongside visual invention to create spaces where past and present coexist. I want viewers to sense that identity is layered, fluid, and evolving, and that personal memory and collective history are intertwined. Even if the cultural references aren’t familiar, the emotional resonance—a feeling of recognition, curiosity, or quiet reflection—remains. I also hope people carry a sense of slowness. The work asks for time, close looking, and allowing meaning to unfold gradually, offering a pause for culture, memory, and one another. Ultimately, if someone leaves more open—to cultural exchange, resilience, and shared humanity—then the work has done what I hope it can.

Q9. What advice would you give to emerging artists who want to work with cultural heritage, historical research, and personal identity in ways that feel both intellectually grounded and emotionally resonant?

I would begin with respect and patience, for the cultures you engage with and for your own process. Working with heritage isn’t about collecting symbols; it’s about understanding context, lineage, and responsibility. Research deeply but also listen to what resonates intuitively. Intellectual grounding comes from curiosity and rigor, not proving something. At the same time, allow space for emotion and personal experience. Uncertainty and questioning can be the most honest place to work from. Let your connection guide how history enters the work, rather than forcing it to illustrate research. Material choices matter: when chosen intentionally, they carry meaning beyond aesthetics and bridge the intellectual and emotional. Resist the pressure to explain everything strong work creates space for reflection and multiple interpretations.

We wrapped up our conversation with Sara, and honestly, I can’t stop thinking about something she’s doing that most of us spend our entire lives avoiding.

We’re taught that growing up means figuring yourself out. Becoming one coherent person. Picking the parts of your background that fit together and quietly letting go of the rest. If you’re from multiple places, you’re supposed to integrate them into something smooth, something that makes sense when you explain it at dinner parties.

Sara never did that. And her work is proof that maybe we’ve been asking the wrong question this whole time.

She grew up between Berkshire, Nigeria, and the North of England. Most people in that position would spend decades trying to resolve it, trying to become one unified thing. Sara just let it all crash together and started painting from the wreckage. British and Nigerian heritage colliding on the same canvas. Not blending. Colliding. And somehow, in that friction, creating patterns that feel more true than anything carefully integrated ever could.

What gets me is the fabric thing. She uses indigo dyed cloth in her paintings not as decoration but like it’s holding memory. Like cloth can remember things people forgot to say out loud. And maybe that’s the point. Maybe memory doesn’t just live in our heads. Maybe it’s in materials, in substances, in the things that touched the people who came before us.

She’s painting with her grandmother’s actual oil paints. Not similar ones. The tubes her grandmother left behind. Which means every painting literally contains her lineage. Not as symbol. As substance. That changed how I think about inheritance completely. It’s not just stories we pass down. It’s physical presence, still here, still active in what we make.

And those connections between Benin and Japan she keeps talking about. Linguistic parallels, spiritual overlaps, craftsmanship techniques that somehow mirror each other across continents that never touched. Most people would treat that as cool trivia. Sara built her entire practice around what it means. Because it suggests the story we’ve been told about which civilizations mattered is way smaller than what actually happened. That human creativity was never limited to the places we’ve been taught to worship.

Here’s what her work actually taught me. The pressure to become one simple thing isn’t about you. It’s about making yourself easier for other people to understand, easier for systems to categorize, easier to explain. But that’s not how identity actually works. You’re not one story. You’re overlapping contradictions. Cultures crashing into each other inside you constantly. And the most honest thing you can do is stop trying to resolve that and start creating from it instead.

Most artists smooth out their complexity before presenting it. Sara doesn’t. She paints from the collision and trusts that the truth in that mess will communicate even when people don’t understand every reference. And she’s right. Because pattern and rhythm speak before knowledge does. You feel her work before you interpret it.

Sara’s work exists because she stopped trying to land. She let herself be complicated and used that complication as the material itself. And if you’re someone who’s spent your life trying to pick one version of yourself, her work is permission to stop. To paint from the collision. To trust that being multiple things simultaneously isn’t confusion. It’s the truth.

Follow Sara from the links below to see what happens when you finally stop trying to become one thing and start creating from everything you actually are.