She Was Five Years Old When Museum Became The Only Place She Could Hide I Olga Hiiva

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve curated enough exhibitions to know this: the work that changes you isn’t always the work that’s easiest to look at. Sometimes it’s the piece that carries so much weight you have to sit with it before you can even begin to understand what you’re feeling.

For our virtual exhibition Faces, we wanted artists who understood that faces aren’t just about features or expression they’re about what gets carried across generations, about the stories written into skin and bone, about the grief and resilience that shapes how we look at the world and how the world looks back at us.

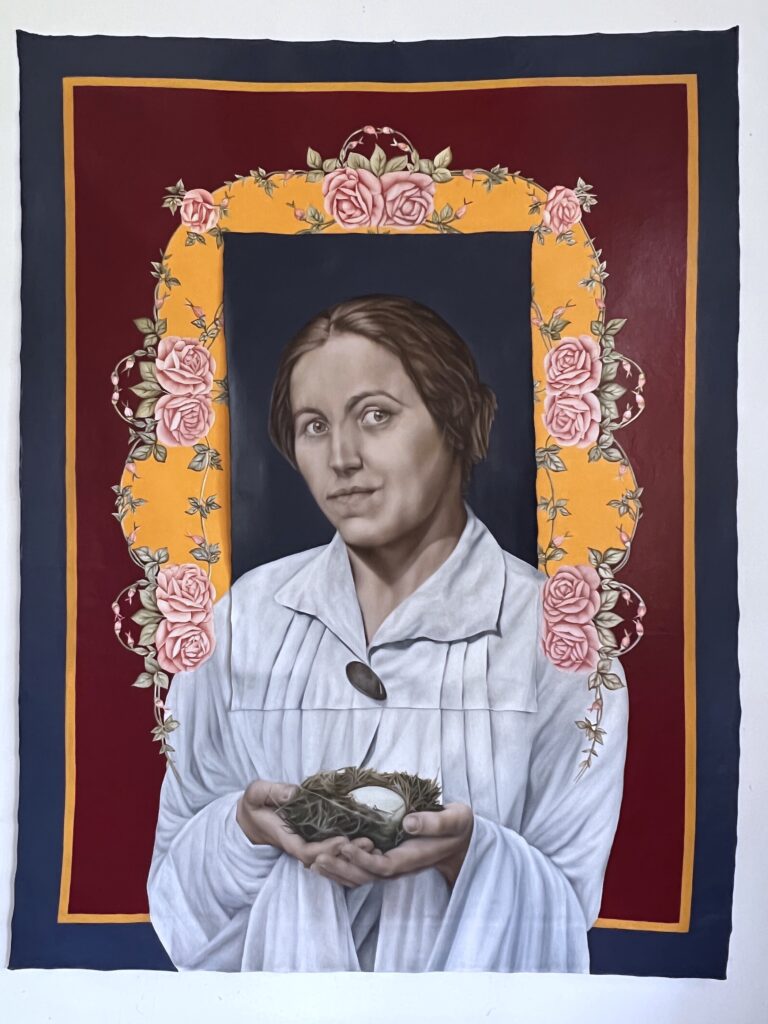

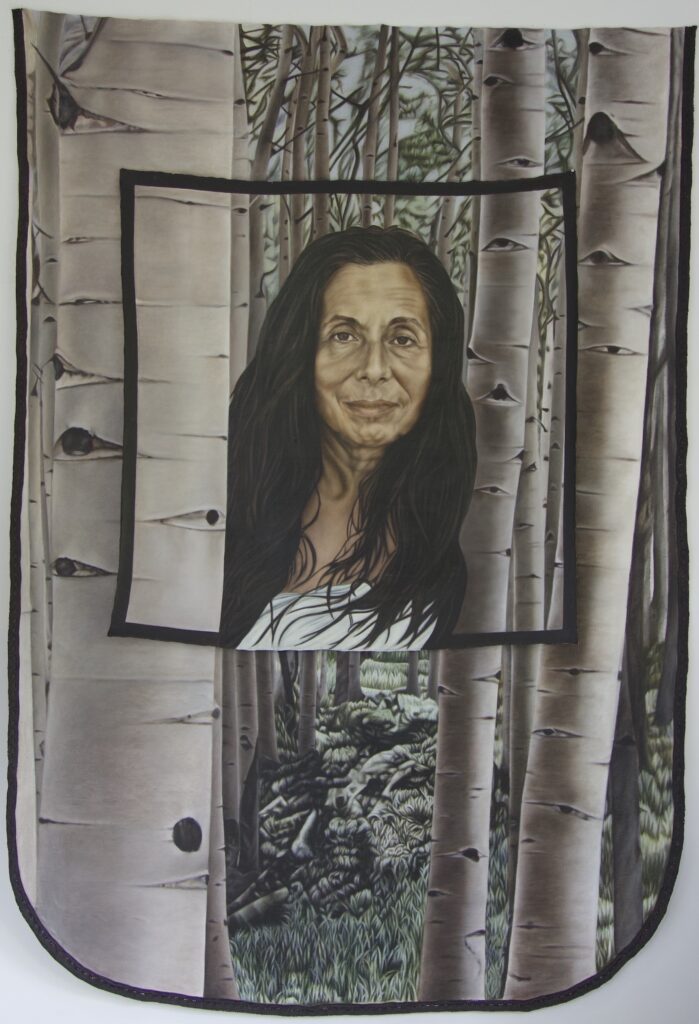

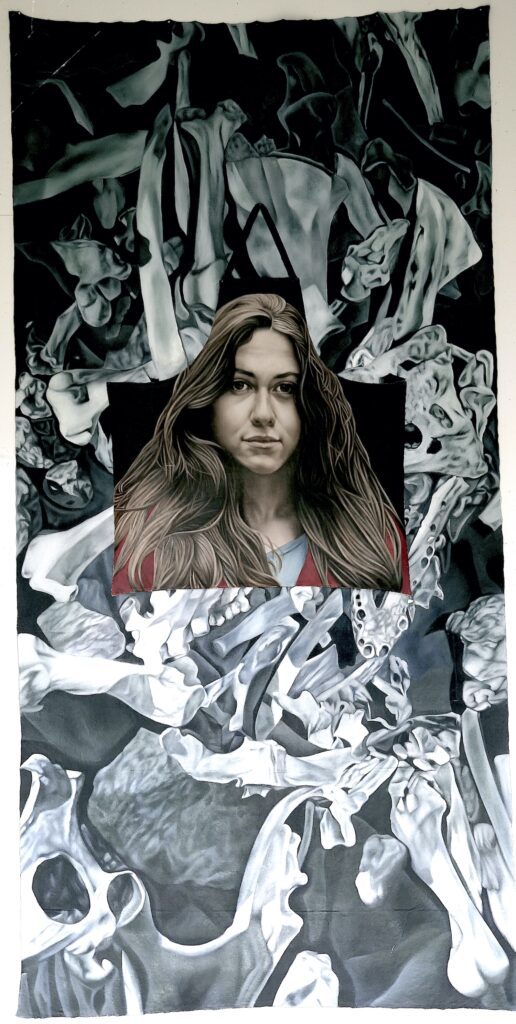

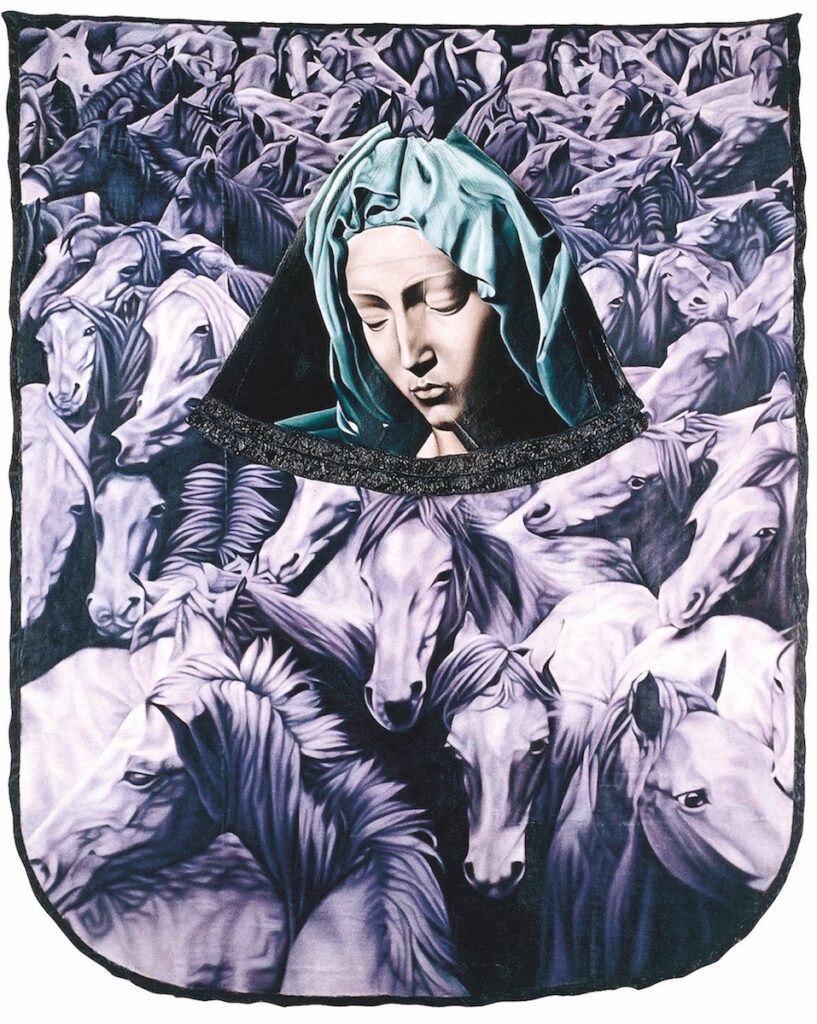

And then Olga Hiiva’s submission arrived, and we realized we weren’t just looking at faces anymore. We were looking at ghosts, memories, absences made visible through paint on fabric that once belonged to someone else.

Her work doesn’t ask for your attention politely. It demands something harder: that you witness what happened to people who were erased, that you hold the weight of stories that were never supposed to survive, that you sit with beauty and violence in the same frame without turning away.

We selected Olga because her work operates on a truth most artists avoid: that the most honest portraits aren’t always of the living, and that sometimes the only way to give voice to what was silenced is to paint it onto the fabric that held those bodies, those tears, those blessings and curses.

Olga grew up in the Soviet Union during a time when regular school was designed as a disciplinary machine strict, stifling, engineered to crush creativity and eliminate any impulse toward self-expression. But her mother worked at the Hermitage Museum, and at five years old, Olga was enrolled in a museum art class that met every Saturday afternoon. For six years, she had an easel, paper, watercolours, gouache, charcoal. She painted still lives and portraits and story illustrations. After class, she and her best friend roamed the palace floors, waiting for their mothers.

The museum became her sanctuary. Not metaphorically literally. It was the one place where princesses could still exist, where beautiful objects were protected, where paintings could tell stories without someone punishing you for listening. That contrast between the world that wanted to flatten her and the world that let her imagine is still the engine of everything she makes.

But there’s a darker foundation underneath that beauty, one you need to understand before you can actually see her work.

Her grandmother perished in Stalin’s death camp. Her mother was nine years old when it happened. This isn’t abstract history it’s family memory, the kind that doesn’t fade because it shaped everyone who came after. When Olga began painting family portraits years later, she wasn’t just making images. She was reaching across decades of silence, trying to paint her grandmother as she was before she was taken, before she knew what was coming, before violence rewrote her story into absence.

She wanted the painting to say something to her grandmother that couldn’t be said while she was alive: You can be at peace now. Your children survived. Your grandchildren are here.

She doesn’t use regular canvas. She paints on old tablecloths, nightgowns, aprons fabric that once touched skin, absorbed sweat and tears and the small rituals of daily life. These aren’t just surfaces. They’re witnesses. Receptacles for emotion that might be abandoned or discarded but still carry the memory of whoever used them. Painting on them isn’t aesthetic choice it’s acknowledgment that some stories live in objects, not words, and the only way to honour that is to paint directly onto what remains.

Her work handles beauty, violence, grief, resilience without trying to separate them. She finds the embroidered details in the fabric flowers, patterns, the decorative work someone’s hands made and incorporates them into the painting. A poet once told her that decorativeness in art is like musicality in poetry. Those elements bring rhythm, create space where your eye can rest even when the subject is unbearable. She also works with questions rather than answers. Why is her grandmother holding an egg? Why are three women walking into a forest? The mystery keeps you engaged without demanding you arrive at a single interpretation.

She’s been teaching art in New York public schools since the 1980s, and here’s what’s striking: she began teaching portraiture before she’d ever painted a portrait herself. She didn’t think it was possible to paint a specific person and stay universal, the way Byzantine icons do. But her students’ kids from everywhere, carrying different faiths and cultures made portraits that were both concrete and abstract. They showed her what was possible. That discovery led to the “icon portraits” she makes now: faces that honour individual lives while carrying collective weight.

Her process is slow, sometimes taking years per piece. She describes it as feeling like a novelist rather than a short story writer. Each painting unfolds at its own pace, and rushing would betray what she’s trying to do. She works across painting, photography, and film using photographs as sketches, creating ritual performances that echo the meanings in her paintings. One medium feed the other, and the cross-pollination keeps the work evolving.

Now, let’s hear from Olga herself about why she paints on fabric that once held other lives, about making beauty coexist with violence without apology, and why the museum wasn’t just where she learned art—it was the only place a Soviet child could hide and still breathe.

Q1. Can you tell us about growing up in the Soviet Union and how you eventually found your way to becoming an artist? How do those early experiences still show up in your work today?

My mother, a researcher, museum guide, and lecturer at the Hermitage Museum, first enrolled me in a museum art class at the age of five, and for the next six years I attended this magical sanctuary where each of us had an easel, large sheets of paper, watercolours, gouache, and charcoal to paint still life’s, portraits, and story illustrations for several hours every Saturday afternoon. Regular school in Russia was a very strict disciplinary environment designed to stifle creativity and self-expression, but the museum offered a rich imaginary world where princesses lived, where beautiful objects shined, and paintings told stories… My best friend and I roamed the palace floors while waiting for our mothers after art class. I believe that during those early years I decided that I would become an artist, and to this day those experiences are a part of my practice, whether assembling and finding cloth objects, painting portraits, or creating performance films.

Q2. Your family’s story especially what happened to the Ingrian-Finnish community is heartbreaking. How does that history live in your paintings? Is it something you consciously explore, or does it just come through naturally?

My family’s story is not unique to the Ingrian-Finnish history in the post-war Soviet Union. However, every family has its own story. My grandmother perished in Stalin’s death camp when my mother was nine. When I embarked on a series of family portraits, the act of painting my grandmother brought me into an awareness of the beautiful, strong, educated woman she was before she was taken away or even knew what suffering lay ahead for her. I wanted the painting to say to her that she should be at peace and that her children survived and her grandchildren are thriving.

Q3. You paint on old tablecloths, nightgowns, and vintage fabrics. What made you start working on these instead of regular canvas? What do these materials hold for you?

A tablecloth, a nightgown, or an apron, as I see it, is a receptacle for tears, shouts, blessings, and curses—a canvas for emotion. They may be abandoned or discarded, but what remains is the memory of a vanished story, of silence, and of hope.

Q4. Your work touches on really heavy themes, beauty, violence, grief, resilience. How do you approach these without making the work feel too heavy-handed or overly explained?

At the borders of scenes of violence, grief, or exile, I find the embroidered handiwork in the material and make it part of the painting. A poet told me once that “decorativeness in art is like musicality in poetry.” The decorative elements in the cloths I use are almost always present in my work. I feel that they help me bring lightness and musicality to the sometimes heavier images. I also strive to lead with a question rather than an answer so the viewer may recognize an element of mystery in an image of motherhood, or in an article of clothing, or in a particular symbol. Why is my grandmother holding an egg? Why are the three dark women walking into the forest? Questions are raised, and the viewer’s attention is engaged.

Q5. You’ve been teaching art in New York public schools since the ’80s. Has teaching changed the way you make your own work? What have your students taught you?

I began teaching portraiture in schools before I ever painted a portrait myself. I did not think that I would be able to create a portrait of a specific person and yet remain abstract or universal, as, for example, in the icon paintings of the Byzantine era. However, my students made incredible life-size portraits that were both concrete and abstract. This discovery of what is possible in portraiture led me to the Icon portraits I am painting today. I have spent years teaching in Queens, famous for its diversity. My students come from countries across the globe. They are Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, etc. In respecting their creative work, I have expanded my own understanding of different cultures. Much of my work is overlay and collage. Engaging with Islamic art, for instance, has taught me to appreciate Islamic decorative patterns and how they can enrich a collage or a painting.

Q6. Some of your work is very personal, but it’s also shown publicly in galleries and exhibitions. How do you navigate that sharing something so intimate with strangers?

When nudity or intimacy is depicted by women, it is often considered personal. However, throughout the ages, painters—mostly male—freely depicted intimate scenes. When I paint or photograph nudes, the figures become archetypal, transcending into a kind of mythological realm. They are symbols of the human condition, just as the cloth and clothing that they are on. Painting can also effect a kind of catharsis. When I painted my grandmother, I felt, in sharing her image with others, I was connecting with a sense of hope.

Q7. You work in painting, photography, and film. Does switching between these mediums change how you see things, or does it all feel like part of the same conversation?

I regard some of my photographs as sketches for a painting. Via projection, I establish scale, determine positioning, and proceed to the drawing phase. The film and ritual performances that I create echo the meaning inherent in my paintings. It is always the paintings that generate a setting for a narration accompanied by movement, dance, music, and poetry. I enjoy the cross-pollination and find it inspiring. One medium informs and enriches the other.

Q8. Your practice unfolds slowly, often across years. How do you stay with a question long enough for it to deepen rather than exhaust itself?

My painting is indeed a slow and labour-intensive process. I often feel like a novelist, rather than a short story writer or a poet. The promise of each painting takes this time to unfold. Some of my pieces do take several years to complete. But there is a throughline. My concept of “icon portraits” leads from one work to the next. Each painting, though stylistically and technically similar, differs in its subject, colour scheme, the material it is painted on, and size. Therefore, I feel that the possibilities are endless and inexhaustible.

Q9. When viewers encounter your work, what kind of attention do you hope they bring intellectual, emotional, bodily?

I hope the viewer will respond emotionally to my paintings. I wish them to absorb, to question, to know how they are feeling, and to walk away with empathy.

Q10. Are there materials, forms, or approaches you feel drawn toward now that reflect where you are in life rather than where you’ve been?

For each painting that I make now, I would like to create a ritual performance to accompany it. I am hoping to install an exhibition of several of my paintings accompanied by performances (dance) and projections of photo images. My recent travels with dancers and musicians to India, Cuba and Mexico have engaged me in photographing indigenous communities, and this has inspired my connection with ritual performance.

Q11. What would you say to artists who are drawn to difficult themes trauma, identity, loss but aren’t sure how to make that work honest without it feeling exploitative or too raw?

One needs to be as true as possible to one’s own identity, experience, and history. Artists who are drawn to these difficult themes are called to give meaning and create a narrative. If the work is honest, it will elicit empathy in those who are engaged with it.

Wrapping this conversation with Olga, I realized something uncomfortable: most of us believe we’d resist erasure if we faced it, yet we can’t even name the people in our own families who were silenced three generations back.

Olga paints her grandmother who died in Stalin’s death camp. That sentence is easy to write; sitting with what it means is not. Her grandmother was meant to vanish completely that was the architecture of Soviet violence. Eliminate the person, eliminate the memory, eliminate the story. Decades later, a granddaughter who never met her picks up a brush and refuses that erasure not by painting suffering, but by painting her grandmother before, when she was still whole. That isn’t sentiment. It’s war against forgetting.

What Olga understands what most memorial art misses is that you don’t honor the dead by depicting their destruction. That lets violence win twice. She paints what was taken, not what was done. She gives her grandmother back her beauty, her future, her wholeness. The camps wanted nothing. Olga paints everything.

What undoes me is that she learned this early. Soviet schools were factories for compliance, designed to crush beauty and self-expression. Yet every Saturday, she went to the Hermitage for art class. While a system worked to flatten everyone around her, she painted watercolors surrounded by proof that beauty could survive inside violence. That wasn’t rebellion. It was survival instinct recognizing the only territory worth defending.

The fabric she paints on reveals something we’d rather ignore objects survive when people don’t. Tablecloths, nightgowns, aprons, these ordinary things outlast bodies and carry memory forward. Painting faces on fabric isn’t aesthetic choice; it’s indictment. Memory lives in what we discard, not what we monumentalize.

Her teaching shaped her practice in a way most artists wouldn’t admit. She learned portraiture from children, not masters. Teaching before painting portraits herself, she discovered—through her students—that a face could be specific and universal at once. That humility became the foundation of her iconoportraits.

Her years-long process isn’t patience; it’s refusal. You can’t rush painting someone back into visibility. Slowness resists the efficiency erasure depends on. Every deliberate layer insists that some work cannot be hurried without betrayal.

Now she’s moving toward ritual and performance painting joined by movement, living bodies activating memory in real time. It’s an acknowledgment that visibility alone isn’t enough. This isn’t art to be passively consumed; it’s art that demands participation, asking us to carry memory forward with our own bodies.

The five-year-old who found sanctuary in a museum didn’t just become an artist. She learned that beauty isn’t decoration it’s defense. Sanctuaries aren’t retreats; they’re refusals. Her grandmother was meant to disappear. Millions were. Yet Olga proves, again and again, that memory survives, beauty survives, and absence doesn’t get the final word.

Follow Olga’s work to witness how remembrance becomes resistance and how the people meant to vanish are painted back into permanence.