When Holding Everything Inside Finally Breaks You & Painting Becomes the Only Way Out | Nena Lang

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve spent enough time curating to recognize when something isn’t just art it’s evidence. Proof that someone survived something by making it visible.

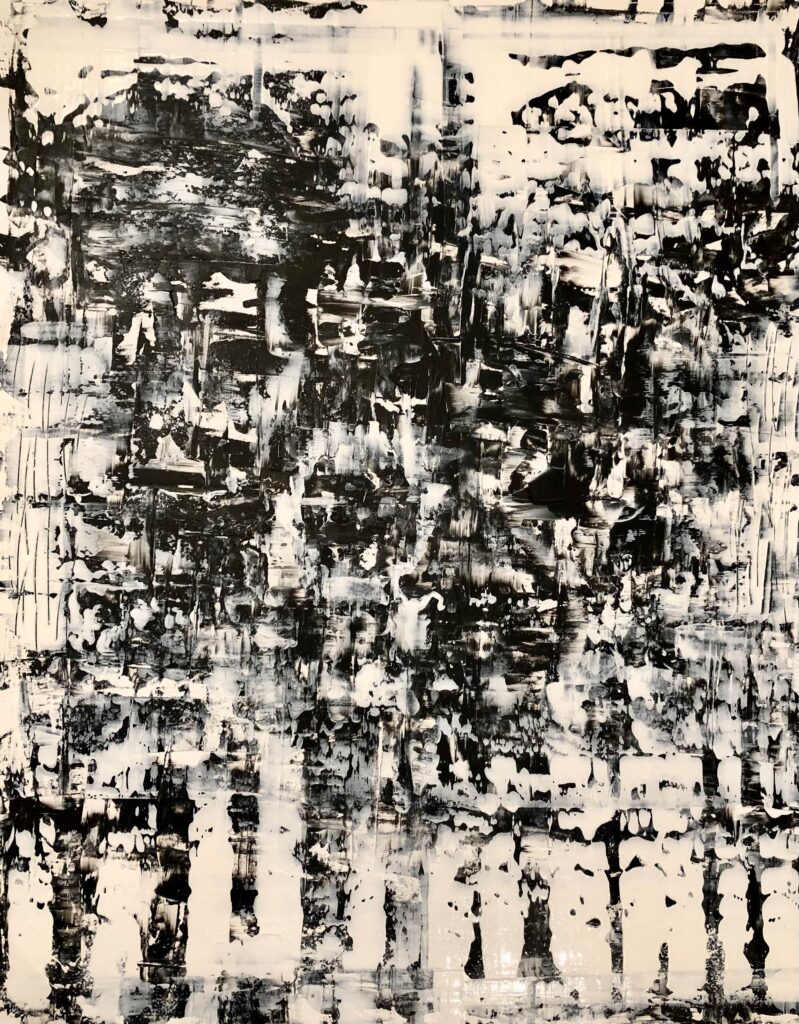

For our Faces exhibition, we invited artists to explore what faces reveal and conceal. We expected portraits, expressions, the visible architecture of identity. What we didn’t anticipate was someone who would make us question whether a face needs features at all whether the truest portrait might be what’s underneath, the accumulated weight we carry that never makes it to the surface.

Nena Lang’s submission arrived, and something about it felt different. Not because it showed us anything we could name immediately. But because standing in front of her work feels less like looking at something and more like being confronted by the physical presence of emotion itself as if feelings could have mass, texture, resistance.

We selected Nena because her paintings refuse to behave. They won’t tell you what you’re seeing. They won’t perform clarity or resolution. They just exist intensely, physically, uncomfortably demanding something from you that most art never asks for.

Before we hear from Nena directly, here’s what you should know: some artists come to their practice through training, through curiosity, through ambition. And then there are artists who arrive because something inside them reached a breaking point, and making became the only alternative to shattering.

There’s something about Nena’s path that suggests the latter. Theatre first, where she learned presence, voice, how to inhabit stories that weren’t hers. But then something shifted some moment when performing other people’s narratives stopped being enough, when whatever she was holding inside demanded its own language.

The way she works is strange. She doesn’t use brushes. She uses palette knives and rulers but not the soft artist spatulas. Hard plastic school rulers. The kind that doesn’t bend. There’s something about needing tools that resist, that push back, that won’t just give in to whatever force you’re applying.

Her paintings are built in layers. But not the kind that create pretty depth. These layers feel like scar tissue each one evidence of something that had to be covered, buried, scraped away, then built over again. Some stay visible. Some don’t. And what you see depends on how long you’re willing to stand there.

She’s made different bodies of work over the years. Early pieces so dense with feeling they’re almost suffocating. Then something opens up space, air, expansion. Then she strips it all back again, removes even colour itself, testing whether structure alone can hold what she’s trying to say.

And apparently it can. The monochromatic pieces are somehow more brutal than the rest. As if removing color removes the last place to hide.

People who stand in front of her work describe feeling it before seeing it. Physical reactions heat, pressure, something tightening in their chest. The body knows before the brain catches up. That’s not normal. That’s what happens when something true enough gets too close.

Now let’s hear from Nena about what breaks when you can’t hold everything inside anymore, and why sometimes the most honest face is the one that refuses to look like a face at all.

Q1. You started out in theatre in Belgrade before moving into painting. What was that shift like for you, and what made you realize painting was where you needed to be?

Theatre taught me how to use my voice and my body, how to be present, how to stand in front of people and communicate directly with them. It taught me what it feels like to be someone else, to carry a story on stage, to exist physically in front of an audience. Painting came later in my life, at a moment when I could no longer hold everything inside. I felt a deep need to release my inner world, to put it somewhere outside of myself, honestly and without control. When I started painting, I felt an urgency I had never felt before. I wanted to paint constantly, almost obsessively. It was a way of exposing and expressing myself without hiding, without roles, without explanations. Through color, movement and layers, I could finally say what I could not say out loud. Painting became a space where I could be raw, vulnerable and contradictory. That is when I understood that this was not a choice. It was something I needed to do. It became my language.

Q2. You work primarily with palette knives and rulers to build up these really rich, textured layers. How did you land on that approach? What can you do with a knife that you can’t do with a brush?

Palette knives became my main tool very early on. I was working with complex, often hidden emotions, and from the beginning I worked in layers. That way of building felt natural to me. A knife allowed me to express those layered inner states physically, through pressure, movement and resistance. It gave me the possibility to build, scrape and reveal at the same time. There are spatulas made for artists, but they felt too soft for what I needed. That is why I started using rulers as a substitute for spatulas. I began with simple plastic geometric rulers, the kind used in school. With them, I could control the angle, the pressure and the strength of each gesture very precisely. I knew exactly how hard to press and under which angle to move in order to achieve the structure and patterns I was looking for. The ruler allowed me to work intuitively, but with resistance and intention. Using palette knives and rulers together helps me give form to complex emotions. My paintings carry a lot of raw emotion, but my mind works through structure, and that is how I hold intensity.

Q3. There’s so much depth in your work not just visually, but emotionally. How do you think about creating that kind of layered experience for someone looking at your paintings?

I do not think about depth as something I need to create deliberately. It happens through the way I work. I build my paintings slowly, in layers, allowing each one to carry its own weight and emotion. Some layers are visible, others are partially hidden, just like in inner life. I want the viewer to enter the painting gradually. At first, there is an immediate emotional reaction, something that is felt rather than understood. Then, if they stay with the work, more begins to reveal itself – textures, traces, interruptions, quieter moments. I am interested in that slowing down, in the moment when looking turns into presence. The layered experience comes from honesty. I do not try to guide the viewer or tell them what to feel. I create space for their own emotions to meet mine. The painting holds what I have put into it, and the rest happens between the work and the person standing in front of it.

Q4. You’ve created several series Whispers of Heritage, Blue Horizons, Circles of Life, Inner Reflections. Do these come from the same place, or does each series ask a different question?

All of my series come from the same inner source, but they reflect different phases of my development as an artist. In the beginning, my work was deeply focused on emotions and inner states. Inner Reflections grew directly from that need – to process what I was carrying inside through strong contrasts and layered compositions. Over time, the work began to open outward. My fascination with the color blue naturally led to Blue Horizons, where space, breath and emotional expansion became central. From there, I felt the need to reduce even further, which resulted in My Monochromatic World, a series focused on texture, shadow and structure rather than color. Later, my attention shifted toward broader questions – cycles, continuity and connection – which found form in Circles of Life. Whispers of Heritage marks a deeper shift toward identity, memory and feminine lineage. It reflects a move from exploring emotion toward exploring who we are and what we carry through time. These series are not separate concepts, but stages of one evolving process. Together, they trace my development as an artist, shaped by experimentation, intuition and an ongoing search for meaning.

Q5. You talk about art going beyond words to touch something deeper. What do you think people feel first when they stand in front of your work before they even try to explain it to themselves?

I think the first thing people feel is emotion and energy. It happens before any thought or interpretation. Something shifts inside them the moment they stand in front of the painting. Many describe it as a physical sensation – a warmth, a pull, a quiet intensity, sometimes even a sense of familiarity they cannot explain. The body responds first, long before the mind tries to understand what it is seeing. For me, that first emotional encounter is essential. I want the work to meet the viewer on that intuitive level, where feeling comes before language. That is where the painting begins to live, and where a real connection can form beyond words.

Q6. Your monochromatic work is so sculptural, all texture and shadow. What happens when you take color away? Does it free you up or make things harder?

Through the monochromatic series, I wanted to see whether it was possible to create powerful, emotionally intense paintings without relying on color itself. Instead of contrast between colors, I worked with subtle variations, different shades of the same tone, texture, shadow and rhythm. Taking color away makes the work more demanding, because there is nothing to hide behind and every decision becomes more visible. Structure, rhythm and surface have to carry the emotion on their own. At the same time, it is freeing, because it forces clarity and sharpens my focus, allowing me to work with greater precision and intention. This approach allowed me to concentrate the emotion rather than dilute it. The strength of the work comes from structure and depth, not from color. For me, these paintings are very strong – reduced in palette, but rich in intensity and presence.

Q7. You’ve shown your work internationally New York, Miami, Venice, Milan including at the Venice Biennale. Has seeing your work in those contexts changed how you understand what you’re doing?

Showing my work internationally made me more aware of how differently the same painting can be received. My work always communicates on an intimate level, but the response is never identical. In some places, certain works resonated more strongly than others, and different audiences reacted in their own way. That experience did not distance me from the work. On the contrary, it made me more attentive. I began to understand my paintings not only as personal expressions, but as part of a wider, global conversation in contemporary art. The work remained rooted in my inner world, but it was no longer confined to it. Exhibiting in different cultural contexts deepened my understanding of how art lives beyond intention – how it enters dialogue with space, audience and time. It strengthened my sense of responsibility and encouraged continuous growth, while staying faithful to my own voice.

Q8. What’s the difference between someone seeing your work online versus standing in front of it in person? Does scale and texture change everything?

When someone sees my work online, they see an image. When they stand in front of it, they experience it. The difference is physical. In person, scale, texture and light change everything. You can feel the layers, the weight of the material, the movement behind each gesture. The body becomes part of the encounter, not just the eyes. My paintings need time and presence. They ask you to move closer, then step back, to slow down. That is where the work really opens and where its depth can be felt.

Q9. You’ve talked about going through tough periods that reminded you why you make art in the first place. How do struggles creative blocks, personal challenges end up shaping the work?

I believe our transformations are visible in the work. That is why art is so personal. Each painting carries traces of change, of what has been processed, released or integrated over time. Creative blocks are part of that process. I do not panic when they appear. I see them as moments that ask for pause, for patience. I allow myself not to know, not to produce, not to force clarity. Sometimes the most important thing is to let things be. Making art means exposing yourself to a wide audience, including parts of yourself you might otherwise want to keep hidden. That vulnerability is what makes the work truthful. Because of that, art is never static. It is alive, shifting and deeply human. For me, painting is not only about creating images, but about allowing transformation to take place and to be seen.

Q10. What advice would you give to artists who are trying to express deep emotions through their work but struggle to put those feelings into words?

Do not try to translate your emotions into words. Let the work carry them instead. Art does not need to explain itself in order to be meaningful. Trust the process and the materials. Allow yourself to work slowly, to make mistakes, to pause when needed. Deep emotions often need time before they find their form. Most importantly, do not create for approval or clarity from the outside. Put onto the canvas what you are carrying inside, even if it feels unfinished or difficult to define. If the work is honest, it will speak in its own way.

As we wrapped our conversation with Nena, I kept thinking about this: most people spend their whole lives learning how to keep their face on how to hold it together in public, how to look fine when they’re not.

Nena’s work is what happens when that stops working. Not because she decided to be vulnerable or make “honest art.” Because she hit a point where containment became impossible, and painting was the only thing that prevented total collapse. That’s not romantic. That’s survival dressed up as practice.

Here’s what most artists do: they feel something, then they figure out how to express it in a way that makes sense to other people. Clean narrative. Clear emotion. Something you can look at and understand immediately. It’s controlled. It’s legible. It’s safe.

Nena does the opposite. She takes whatever’s inside her messy, contradictory, half-formed, still raw and forces it out through tools that resist her. Hard plastic rulers that won’t bend. Knives that scrape and gouge instead of glide. She’s not trying to make it beautiful or understandable. She’s trying to get it out before it destroys her.

And what that looks like is layers. Not decorative ones. Layers like sediment, like evidence. Each one carrying its own weight, its own truth that contradicts the layer before it. Some get buried. Some resurface. Some exist simultaneously even though they shouldn’t be able to. That’s not technique. That’s what emotional honesty actually looks like when you stop editing it.

Most of us edit constantly. We feel ten things and express one. We carry contradictions and perform coherence. We’ve been trained to believe that growth means resolving those contradictions, becoming more integrated, more whole. Nena’s work suggests maybe that’s bullshit. Maybe wholeness is a lie we tell ourselves because the truth that we’re just accumulated layers of unresolved feeling is too uncomfortable to live with.

Here’s what nobody tells you about creative blocks: sometimes they’re not the problem. Sometimes they’re your body saying, “stop producing and start processing.” Nena doesn’t panic when they hit. She waits. Let’s things settle. Trusts that the next layer will come when it’s ready. Most artists would call that lazy or unprofessional. She calls it necessary. Because forcing output before you’re ready doesn’t create honest work it creates performance.

Follow Nena from the links below to see what faces actually look like when they stop lying when they admit that underneath the performance is just layers of feeling we’ve been taught to hide, and maybe the bravest thing you can do is let them show.