What Does It Feel Like to Hope Your Art Finds the Right Home? | Sally Edmonds

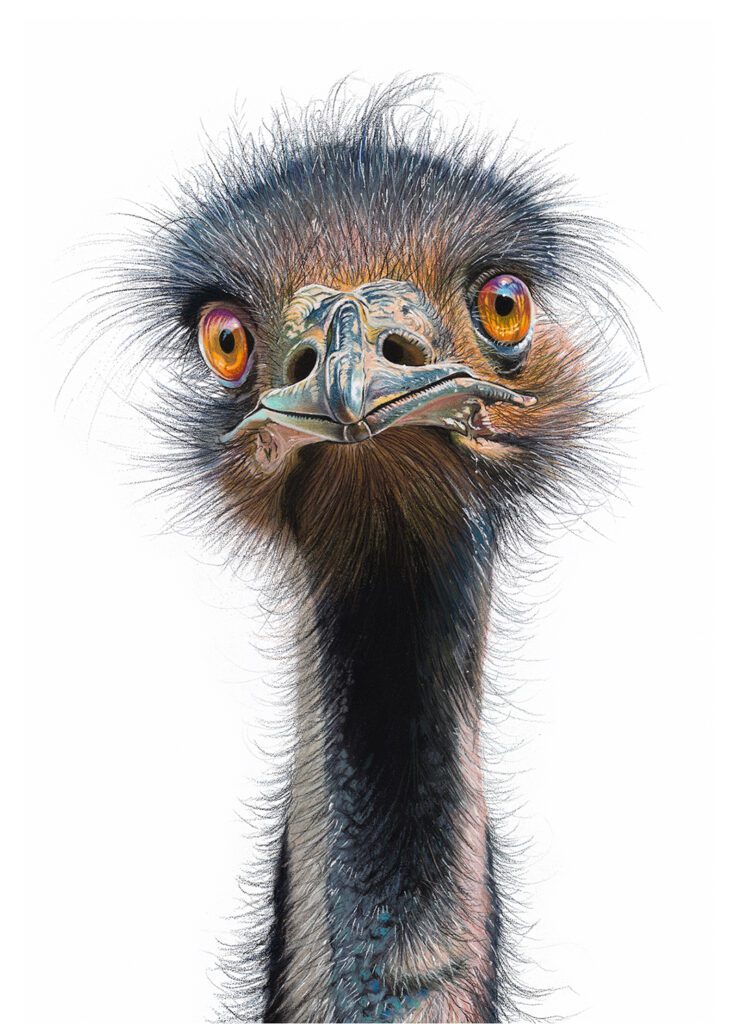

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve learned that the most compelling bird paintings aren’t always the ones with elaborate backgrounds or dramatic natural settings. Sometimes the most powerful work comes from artists who strip everything else away and let the bird itself stand alone and command your full attention.

For our Birds exhibition, we were looking for artists who understood birds not as decorative subjects to place in pretty landscapes but as individual beings with their own presence and personality. We wanted work that made you stop and actually see a creature you might have been walking past your whole life without truly noticing.

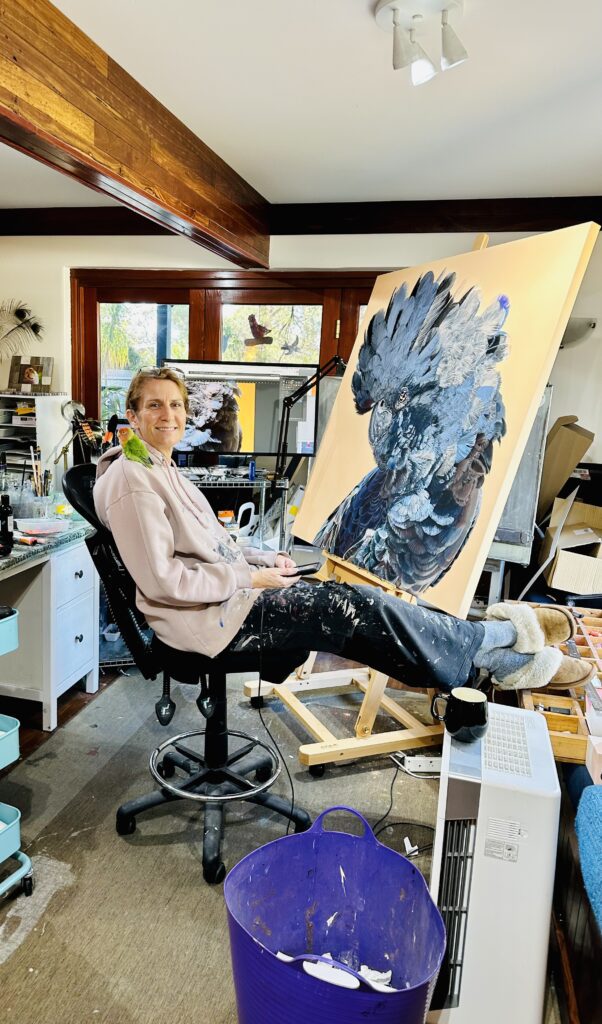

Sally Edmonds’ work arrived in our submissions with an intensity that immediately set it apart from traditional bird illustration. Her birds don’t sit politely waiting to be admired from a comfortable distance, they look directly at you with something that feels close to recognition, holding their ground with unmistakable character.

We selected Sally because her approach fundamentally differs from how most artists paint birds. She’s not documenting species in natural habitats or creating beautiful scenes that happen to include wildlife, she’s after something harder to capture, which is the specific personality and presence of each individual bird.

Before we hear from Sally directly, here’s what makes her approach distinctive.

Sally came to fine art through an unconventional path that included years working in graphic design and pre-press, which gave her a particular eye for composition and the strategic use of negative space that shows up clearly in her paintings. There’s a precision to how she structures each image, a deliberate choice in how she positions elements that comes from training in visual communication rather than traditional fine art education.

She also grew up with birds as constant companions rather than distant subjects to observe, her father kept finches and canaries and chickens and even a tame magpie, so from childhood she was around these creatures in a hands-on daily way that most bird painters have to work years to develop. That early familiarity gave her an understanding of how individual birds actually move and hold themselves and express personality through small physical details that casual observers typically miss entirely.

Her serious painting practice began almost accidentally when she found herself bored working reception and spending hours online looking at bird photography, until one day an image of an egret compelled her strongly enough that she had to paint it. Six months of work later, that painting won an award in a local art competition, which gave her the momentum to keep going and eventually build what’s become her full artistic practice.

What’s immediately noticeable about her technical work is how she handles extreme detail within carefully composed negative space. She works across multiple mediums including pastel, colored pencil, watercolor, and more recently acrylic inks on canvas, choosing based on scale and what each medium allows in terms of building up precise marks layer by layer. She’s very clear about not being a loose painter, she loves detail and clean lines and approaches composition with the same careful attention her graphic design background trained into her thinking.

Her signature approach is presenting birds against completely pared-back backgrounds with no landscape context whatsoever. This isn’t about taking shortcuts or avoiding complex compositions, it’s a deliberate philosophical choice about what she’s trying to communicate. By removing every element except the bird itself, she forces viewers to engage with it as an individual rather than as part of a decorative natural scene, to actually notice the character and specific presence that gets lost when your attention is divided across an elaborate setting.

There’s also a deeper layer to how she thinks about birds that has to do with evolutionary time and survival. She sees them as creatures carrying ancient history forward, beings whose physical forms still show traces of dinosaur ancestry, survivors from eras almost impossible to comprehend. That perspective seems to inform how she renders them, not as delicate decorative creatures but as resilient beings that have persisted through unimaginable spans of change.

She’s actively engaged with local wildlife rescue centers, both photographing birds there for close reference and donating proceeds from her print sales back to support their conservation work. That direct involvement means she knows many of the specific birds she paints personally, has spent time observing them as individuals, which clearly shapes how she approaches capturing their character rather than just their species characteristics.

Now let’s hear from Sally about what changes when you paint birds you actually know as individuals, why she deliberately removes all landscape context, and what it means to build a practice around painting the one thing you’re genuinely obsessed with.

Q1. Going back to the beginning, what first drew you to depict birds and wildlife, and how did that passion evolve into your artistic practice?

I grew up with birds around me at home; my dad kept finches and canaries, chickens and a tame magpie, and I have loved drawing and painting since I was small. I moved permanently to Australia in 2012. My husband had a smash repair company and I worked on reception. It was so boring that I surfed the internet a lot. I looked at art and at birds and then one day I saw a beautiful photo of an Egret and I felt that I had to paint it. I was given permission to use it as reference and the results, 6 months later, won an award in a local art prize. That spurred me on to the next thing and the rest is history.

Q2. You initially built a career in graphic design and pre-press before focusing full-time on art. How did your background in design influence the way you think about composition and detail in your bird paintings?

It very much affects the way I compose images. Also, I gained training in various software packages which has also helped me to design each painting before I start putting it down on canvas or board. I love detail and I am definitely not a ‘loose’ painter. I like clean lines in almost everything; clothes, interiors, art and anything visual. I give consideration to the negative space in my artworks as much as the mark making itself. I also have a very pared back approach to the image. I leave the beautiful settings and landscapes to other bird artists and focus just on the bird.

Q3. You work across pastel, coloured pencil, watercolour, and occasionally acrylic. What factors determine your choice of medium for a particular bird or scene?

Often it comes down to size. I have done some massive pastels before and it’s great but messy and very expensive to frame as I have to use non reflective glass, nothing else is as good. I have actually recently made a big shift into acrylic inks on canvas when I want to paint a large artwork. I love the opportunity for layering colour upon colour that acrylic inks give me. They also work well with my tiny detail brushes. I still work in pastel and pencil but not as much. The watercolours are fun occasionally, usually for small works and particularly on holiday when I love to play. I respect anyone who paints well with them. They are very challenging.

Q4. Many of your works present birds against pared-back or neutral backgrounds. How do you use negative space to enhance the impact of your subjects?

For me it is all about the bird. I want to get the character across to the person looking at the painting. All birds, whatever kind they are, have their own individual personalities. You never know that unless you spend a lot of time with them. I think my graphics background probably plays into this too as well as my love of clean lines and spaces. Most of all I want the viewer to feel a connection. There has been a tendency to think of birds as ‘just a bird’. This is so wrong. If someone loves birds as much as me I hope they feel the bird’s character and if they don’t, I hope it gives them pause to do a double take. Even if they feel that the bird is cheeky, angry or something like that, it’s a breakthrough. Birds in all of the beautiful bird illustrations painted through the decades don’t seem to do that somehow. Maybe it’s just me! I take them out of the landscape and let them stand alone.

Q5. You’ve spoken about birds as survivors from “a time before time” how does this sense of deep evolutionary history shape your interpretation of their presence on canvas?

Every time I paint a foot, I see their ancestry right there in the shapes and textures. They are an incredible story of survival. What is also fascinating is that all the songbirds in the world originate from Australian ancestors. It is likely that a lot of the dinosaurs actually had feathers. Pretty cool that they are still around. I have at least one bird living with me that thinks she is a T Rex.

Q6. Your detailed studies invite close looking. When you paint a species such as a Black Cockatoo or wren, what qualities do you most want a viewer to notice and remember?

I love a painting to look striking from afar and that is often down to colour and form. Then I hope the viewer comes closer for the detail. I like building layer upon layer, line upon line, colour on top of that and then more of the same. I think that people appreciate seeing the work and something they couldn’t easily do themselves, they seem to value that. I love the beginning and the end of a really big painting. I can really lose myself in all those lines and it’s bittersweet when It’s over. I don’t really ever spend much more than 6 weeks on a big piece but in that time it’s like you form a relationship with it. I have some really lovely collectors and I’m always glad when a piece goes to someone that I know will cherish it. It sounds super cheesy, but each artwork comes from the heart and has a bit of me in it. I paint the thing I love and I think it shows.

Q7. You support local wildlife rescue centres through your print sales. How does your engagement with conservation programmes shape your creative purpose?

One thing it does is allow me access to photograph birds close up so there is quid pro quo in that. I am so grateful to our volunteers for the selfless work that they do. Close up photography can really affect what I paint but also I know each bird personally and that informs the way that I paint them. If I do a painting from a bird at a centre, I have the final piece photographed and then if any prints sell through my website, I donate the profits. Also I donate to their auctions. It’s nothing compared to what the volunteers do but it helps. It also gives me an opportunity to spread the word about them and to meet some amazing people.

Q8. Critics often note that your work captures both realism and expressive presence. How do you think about the relationship between faithful observation and artistic interpretation?

There was a trend a while back to put a reference photo next to an artwork to show how alike they were. I thought that was a weird thing to aim for. I’m happy to say that I don’t feel bound by any reference. It’s a good framework to hang my interpretation on. I love letting loose with colour and inventing light and shade to suit me. I probably exaggerate colour a fair bit to be honest. A lot of the photos I use are not very sharp. (I’m better at painting birds than photographing them.) I don’t need reference for each individual feather, just a roadmap to start from.

Q9. How do you feel when viewers respond to your work do they see what you intend, or do they bring unexpected interpretations to the work?

Generally, they respond in the way I had hoped for but how they feel is between them and the painting. If someone gets something different to me then that’s even better. Often when I hear from collectors they speak about their painting like it is a friend or family member in their home. I really like that.

Q10. What advice would you give to artists who are passionate about wildlife and want to build a practice that honours both technical skill and emotional connection to the natural world?

First of all, know your subject. Paint the thing that you love the most and you’ll never get tired of it or run out of ideas. Get out and visit or observe the creatures that you like. It helps to be totally obsessed of course.

As we wrapped our conversation with Sally, what I’m taking away isn’t about technique or process. It’s something she mentioned almost casually, that collectors often talk about her paintings like they’re friends or family members living in their homes rather than just objects on walls.

That’s not how most art gets talked about. Usually it’s aesthetic value or investment or how well it works with the decor. But Sally’s work apparently creates actual relationships. People connect with the bird in the painting like it’s a presence rather than just an image.

That only happens when you’re painting something you genuinely know and care about deeply. Sally isn’t making beautiful bird illustrations. She’s communicating the actual personality of specific birds she’s spent time with and observed closely enough to understand as individuals.

What struck me most is how she talks about reference. There was apparently a trend where artists showed their reference photo next to the finished piece to prove how accurately they’d copied it. Sally thought that was strange. For her, reference is just a starting framework. She exaggerates color deliberately, invents light and shade, works from photos that aren’t even sharp because she doesn’t need perfect detail for every feather. Just enough to build from.

That freedom comes from knowing your subject so well you don’t need to copy. Sally grew up with birds, spent decades observing them, works with wildlife rescue centers where she gets to know individuals personally. All that knowledge means she paints from understanding rather than replication.

The other thing is her complete lack of interest in traditional bird painting with elaborate natural settings. She strips all that away because she wants you to connect with the bird itself, to see its individual character rather than just appreciate a pretty scene. That comes from believing we’ve been trained to see birds as just birds, interchangeable parts of nature rather than beings with their own presence.

Her work is trying to change that. To make you stop and actually look. And based on how people talk about her paintings, it’s working.

Here’s what Sally’s practice teaches. If you want work that genuinely connects, paint what you’re obsessed with. Not what might sell or what’s trending. Paint what you love so much you’ll never run out of ideas. Get close to it. Know it well enough to interpret rather than copy.

And trust that if you paint with genuine care for the subject itself, that comes through. People respond to authenticity even when they can’t name what they’re responding to. Sally paints birds because she’s genuinely obsessed with them, and that shows in every detail. That’s not fakeable. That’s what happens when you commit to what you actually care about.

Follow Sally from the links below to see birds painted by someone who knows them as individuals, and proof that sometimes the most powerful way to honour a subject is stripping away everything except the thing itself.