When Life Experience Makes You a Better Artist Than Talent I Tanya Shark

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve seen thousands of portraits over the years. Beautiful faces, expressive eyes, technical mastery. But we’ve rarely seen work that makes you stop mid-scroll and think: “Wait. Is that me?”

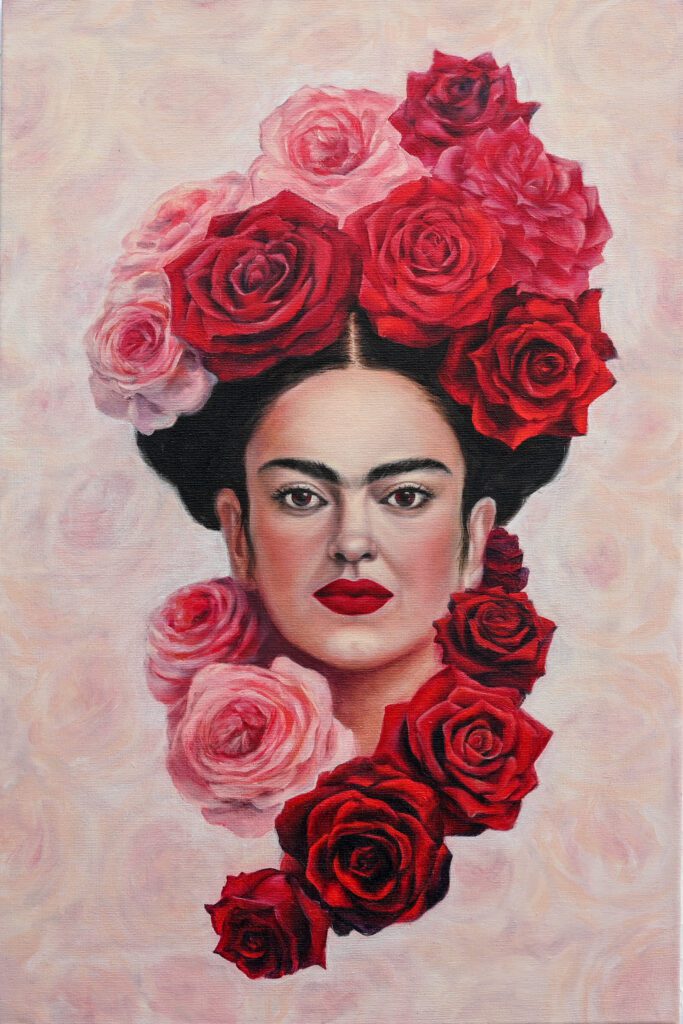

For our virtual exhibition Faces, we wanted artists who understood that faces aren’t just about features they’re about recognition. About seeing something in a painting that you didn’t expect to feel. And then Tanya Shark’s submission arrived, and we realized she’d figured out something most portrait artists never touch: the people who recognize themselves most in her work aren’t looking at human faces at all.

They’re looking at animals. We selected Tanya because she doesn’t paint what you think she’s painting. Her rabbits, cats, and creatures with impossibly knowing eyes aren’t just animals. And viewers keep messaging her saying the same thing: “I saw myself in that painting.”

Now let me tell you about an artist whose story will make you question everything you’ve been told about when it’s “too late” to start.

Tanya started drawing before she could speak. It became her first language, her way of understanding the world before words existed. She trained formally at the Zhostovo School of Painting, learned traditional techniques, built foundations most artists never access. But then life happened. Decades passed. Painting became the thing she used to do, the dream she’d always meant to return to but never found the “right time” for.

At 50, she picked up a brush again. Not because she suddenly had permission or endless time or a gallery waiting. She came back because she couldn’t ignore it anymore. And here’s what makes her story different from every “it’s never too late” cliché you’ve heard: she didn’t come back empty-handed.

For years, she’d been working as a hair colourist. A completely different field. Or so it seemed. But something about working with colour, form, and subtle nuance every single day helping people feel confident through the smallest shifts in tone was training her eye in ways she didn’t realize. When she returned to painting, she brought all of that with her.

She works with oil and glaze techniques, building layers with patience most younger artists don’t have. Her subjects range from contemplative compositions to animals that seem to look straight through you. And there’s something about those animals the way they hold themselves, the tilt of their heads, the emotion in their eyes that makes viewers stop and recognize something they can’t quite name.

Her path wasn’t linear. It wasn’t the story we’re taught to celebrate the prodigy who never stopped, the dedicated artist who knew from childhood and never wavered. Her story is messier, more human, and ultimately more honest: passion, life pulling you elsewhere, decades passing, and then the courage to return when everyone says your best years are behind you.

What she brought back with her the years of working with colon professionally, the experience of living through everything those decades hold, the clarity that only comes from knowing what’s worth caring about that’s what makes her work different.

Now, let’s hear from Tanya herself about what it means to return to your passion when culture tells you it’s too late, about what animals reveal that human faces hide, and why the years you spend away from art might be the exact preparation you need to finally create work that matters.

Q1. Can you share your background and how starting to draw even before you spoke influenced the way you see and interpret the world visually?

It became my first way of understanding the world.

Q2. You trained with the Zhostovo school of painting and have worked with pastels, watercolour, and oil. How does that mix of traditional training and self-driven practice influence your formal choices today?

Studying at the Zhostovo School gave me a solid foundation, and working independently in various techniques taught me freedom and intuition. Together, they shaped my style.

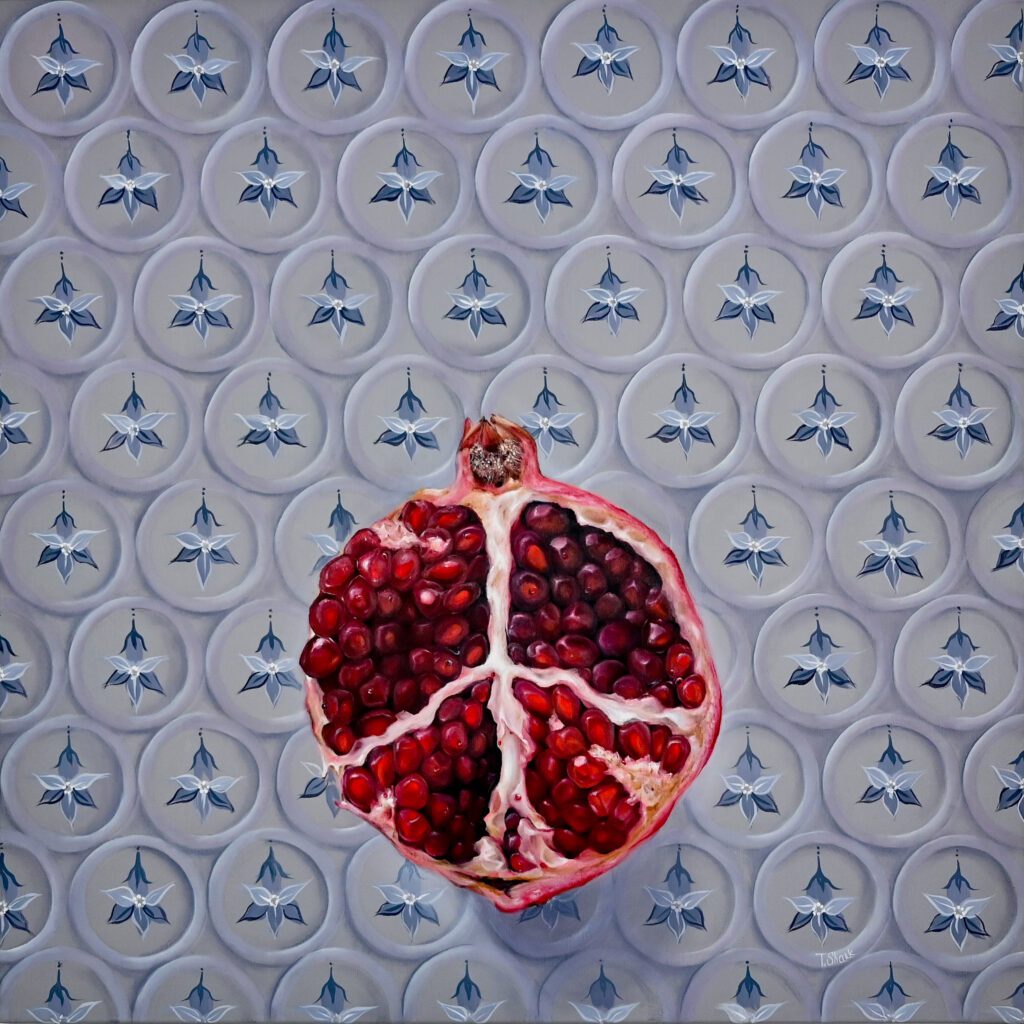

Q3. Much of your work uses oil painting and glaze techniques to create realism with subtle surface presence. How do you balance the precision of realism with the emotional or expressive potential of paint?

I use realism as a structure, not a constraint. Precision lends clarity to the work, while layers of oil and glaze allow space for mood, emotion, and subtle nuances.

Q4. Many of your works whether Diptych Emerald Fish or Whispers of Sunlight suggest calm, contemplative states. How do you think about mood and atmosphere when you begin a composition?

I usually start by thinking about the feeling I want the piece to evoke. Mood and atmosphere guide my choices of color, light, and composition, letting the work unfold around the emotional core rather than just the subject.

Q5. Your work has been noted by commentators for its depth of colour and form. When someone responds emotionally to a piece, how do you understand that kind of resonance?

I view emotional reactions as the bridge between a work of art and the viewer. My second profession is as a hair colorist, where I use style, form, and subtle color nuances to help each client feel confident and satisfied. I approach painting in a similar way—tuning in to emotions.

Q6. Many artists balance intuition with discipline. How do you navigate that balance in your own practice especially in rigorous techniques like glazing and layered oil work?

For me, discipline and patience aren’t problems—they’re part of the joy. I especially enjoy glazing, improving each layer and savoring both the process and the visual result, letting intuition guide me within a structu.

Q7. Realism can be both technically demanding and emotionally rich. What aspects of realism do you find most rewarding and which do you find most challenging?

What I love most about realism is bringing color, light, and texture to life, and capturing not just how things look, but how they feel. The challenge is keeping that balance—being precise without losing the emotion and energy that make the painting feel alive.

Q8. You create and offer prints as well as originals. How do you think about the accessibility of your work, the experience of viewing a print versus the presence of an original painting?

Sometimes I create reproductions of famous works in my own style, which helps me learn and experiment. But the true life of my ideas and emotions is revealed in my original paintings. There’s nothing better than looking at an original painting—its texture, depth, and brightness are perceived in a completely different way.

Q9. You also depict animals with personality and presence, from cats to rabbits. What role do these living forms play in your creative world as subject, companion, or metaphor?

To be honest, I don’t paint animals—I paint people in animal form. Very often, viewers recognize themselves in these works.

Q10. You started painting again in your 50s after a long pause. How has your creative purpose evolved since that return and how does age or life experience shape what you choose to paint?

I’ve always wanted to draw, so at 50, I returned to painting. I have two passions in life: hairdressing and painting. Working with color in hairdressing has honed my eye and my love for the shades I use in my work.

Q11. What advice would you give to artists who are rediscovering creative practice later in life, or returning to a childhood passion after time spent in a different field?

I would encourage them to follow their curiosity and joy, not pressure or expectations. Returning to creative practice as a mature artist is a gift: you bring your experience, perspective, and patience, and that can make a big difference.

Talking with Tanya, I realized something that most conversations about “late bloomers” completely miss: she didn’t bloom late. She bloomed when she was ready.

There’s this narrative we love about artists who start young and never stop the prodigy, the dedicated, the one who knew from childhood and never wavered. We celebrate that path because it’s linear, predictable, easy to understand. But Tanya’s path is the one most people actually live: you start with passion, life pulls you elsewhere, and decades pass before you find your way back. The question isn’t whether that’s valid. The question is: what do you bring back with you when you finally return?

Tanya brought everything. Twenty-plus years of working as a hair colorist, training her eye to see what most painters never develop that color isn’t decoration, it’s emotion. That the smallest shift in tone changes how someone feels about themselves. That precision in service of making someone feel seen is completely different from precision for its own sake. She didn’t waste those years away from painting. She was building the exact skillset that would make her painting matter when she came back.

And then there’s what she said about animals: “I don’t paint animals. I paint people in animal form.” That’s not a metaphor. That’s diagnosis. She’s identified something most portrait artists spend careers missing that we’re more honest when we’re not looking at our own faces. Remove the human features and what’s left is pure emotional posture: the tilt of a head, the softness in eyes, the body language we can’t fake when we think no one’s watching. Her viewers recognize themselves because she’s painting the truth under the performance. The self we are when we’re finally alone.

What won’t leave me is the timing. She came back at 50 the age when culture tells women especially that their best years are behind them, that visibility fades, that opportunities close. She returned anyway, not with desperation or regret, but with clarity. The patience to work in layers. The discipline to enjoy the slowness of glazing. The confidence to start a composition with feeling rather than subject. Those aren’t skills you learn at 25. Those are gifts that only come from living long enough to know what’s performance and what’s real.

There’s also something quietly radical in how she balances formal training with self-taught freedom. The Zhostovo School gave her structure, but working independently taught her intuition. Most artists have one or the other either rigid training that kills instinct, or total freedom that lacks foundation. She figured out how to hold both, which is why her work has technical precision without coldness, emotional depth without chaos.

What Tanya’s practice proves: the years you spend away from your passion aren’t lost time. They’re preparation you didn’t know you were doing. Every skill you build in another field, every year you live, every time you learn to see differently it all comes back with you when you’re ready. And sometimes the most powerful work comes not from the artists who never stopped, but from the ones who stopped, lived an entire other life, and returned with something they couldn’t have made when they were young.

The real gift of starting later isn’t experience it’s freedom from needing to prove anything. Tanya isn’t painting to build a career or earn validation. She’s painting because she finally stopped waiting for permission. And that freedom from performance, from pressure, from the need to be anything other than honest is what makes her animals look back at us and show us who we actually are.

Follow Tanya from the links below to see what happens when decades of living finally become decades of knowing.