Seeing a Leonardo da Vinci Painting in Real Life Changed How She Saw Art Forever I Jennifer Holmes

Most artists will tell you their work is personal. But there’s a difference between making something personal and making something that invites others in. One is a closed door. The other is an open window.

For our virtual exhibition Birds, hosted on Women in Arts Network, we selected artists who understood that birds aren’t just beautiful subjects they’re carriers of meaning, transformation, the tension between staying grounded and taking flight. Among those artists, Jennifer Holmes’ work stopped us in our tracks.

Her paintings don’t perform. They don’t announce themselves or demand attention. There’s a quietness to them, a softness that feels intentional. Flowers, animals, smoke, water she places these elements together in ways that create tension and balance at once. A pomegranate sits beside a stoic face. Light falls on a stem. You pause. You wonder why that pairing, why that contrast. And that wondering is the point.

We selected Jennifer because she doesn’t paint to tell you what to feel. She paints to make space for whatever you bring with you. Her work carries softness and mystery as an invitation for you to bring your own story, to find meaning in the space between feeling and reflection.

Before you get to read the conversation we had with Jennifer, let me tell you something about her.

Jennifer grew up in South Africa, where her art education planted a deep love for detailed, realistic work Renaissance masters, Romanticism, the Pre-Raphaelites. That foundation shaped how she sees. Moving to Berkshire years later opened something else: access to world-class museums and galleries across the UK and Europe. She remembers standing in front of Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna of the Rocks at the National Gallery for the first time. It felt like meeting someone she’d only heard stories about. The presence, the mastery overwhelming in the best way.

For 18 years, she worked as a graphic designer. Built a career, financial security, a life that functioned well. But creative fulfilment? That was missing. Graphic design and fine art are different creatures. Design demands limits, predictability, minimalism. Painting demands the opposite openness, risk, the willingness to not know where you’re going. When she finally made painting her primary practice, it wasn’t about leaving design behind. It was about giving herself permission to explore without predetermined outcomes.

Her process is meditative, almost obsessive. Most of her painting ideas begin with a feeling. The composition appears in her mind nearly complete, but she doesn’t rush to execute it. She sits with it weeks, sometimes months playing with different symbols, refining what needs to be said. She doesn’t search for references immediately or let outside voices in too early. She protects the idea until it’s strong enough to stand on its own.

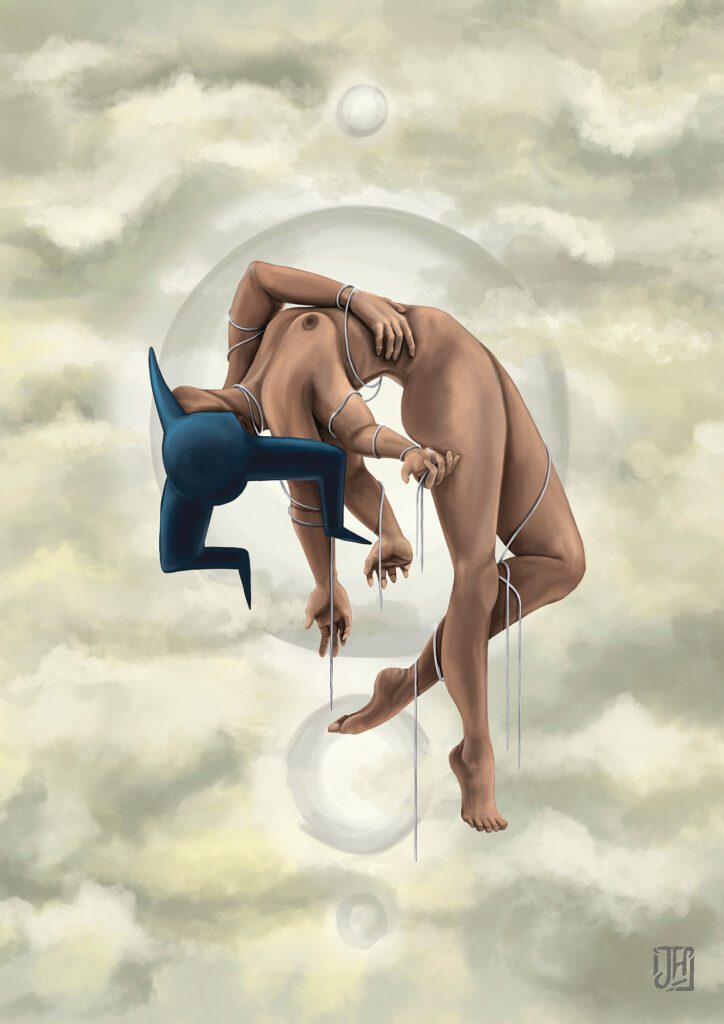

Between 2015 and 2020, her work took on a darker tone fantastical, surrealistic, mystical. She loved that otherworldly quality, but she started noticing something underneath. The darkness wasn’t just aesthetic it was a mirror. She was battling depression and anxiety, and her paintings were showing her what she couldn’t yet name. With therapy and real work, she healed. And her art transformed. Now it reflects her focus on healing, on the importance of that inner world each of us carries. She sees art as a language, an opportunity to connect with others, and her work offers space for people to access their own introspection.

She also creates limited run linocut prints. The tactile, repetitive carving process soothes something in her. The reduction and simplicity of linocuts offset the complexity of her paintings, helping her see the bigger picture in her ideas. It’s a balance between her past as a designer and her present as an artist.

Now, let’s hear from Jennifer herself about how she builds stillness into narrative, and why beauty isn’t decoration it’s the bridge that connects us.

Q1. Growing up in South Africa and later building a studio life in Berkshire, how have these two places shaped the visual language that continues to appear in your work?

My art education in South Africa was foundational but helped nurture my deep love for detailed and realistic fine art, particularly the Renaissance, Romanticism, and the Pre-Raphaelite eras. Building a studio life in Berkshire has opened up a different kind of education — one shaped by regular access to world-class museums and galleries, both in the UK and throughout Europe. I’ll never forget seeing Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna of the Rocks at the National Gallery for the first time; experiencing it in person was a pivotal and awe-inspiring moment felt like meeting a revered figure. The sense of presence and mastery was overwhelming. Being surrounded by art that has endured through centuries continues to shape my practice today.

Q2. After 18 years as a graphic designer, what shifted in your creative process when painting became the primary focus of your daily practice?

As a graphic designer I have built a good life, a career and financial security for myself. But I have never felt creatively fulfilled. Graphic design and fine art are very different disciplines. When I’m painting, I need to open up and explore. I need to be able to experiment and risk failure in order to grow as an artist. The outcome is often unknown. In many ways, it’s the perfect antidote to graphic design; where I’m working within stringent limits, the outcome is predefined and predictable and the goal is minimalism.

Q3. Flowers, animals, smoke, and water often share space in your compositions. How do you decide which elements belong together in a single painting?

Most of my painting ideas begin with a feeling. Usually the composition appears in my mind almost fully formed. Over weeks or even months, I will play with different subjects in the composition to help better express the feeling or ideas symbolically. Some symbols are personal to me, some are more universally known. What’s great about this approach is both can work to serve either my idea or narrative or the viewers own interpretation. I also like to inject contrast, through colour or object, where I think it will help emphasise visual drama or interest. In one painting, I filled the background of my subject with pomegranates. I couldn’t get enough of placing the vibrant red and greens together and felt it really helped contrast the stoic expression of the model at the centre.

Q4. Many of your recent works explore spiritual and emotional healing. What led your subject matter in this direction at this stage of your life?

Between 2015-2020 I was creating more fantastical and surrealistic work. While I really enjoyed the mysticism and otherworldly nature of this work, I was seeing a darkness to it all that led me to realise I was battling depression and anxiety. With extensive therapy and hard work, I am much healthier and happier. My work now reflects my focus on healing and the importance of that ‘inner world’ that each of us has. My journey has been transformative and I’m so grateful for it. I believe art is a language and opportunity to connect with others and my work looks to offer space for others to access their own introspection.

Q5. There is a softness and quiet mood running through much of your figurative work. How do you balance stillness with narrative when building an image?

I think much of this comes from the meditative way I build my compositions in my mind. I don’t go looking for references or any ‘outside help’ until I’m sure of what I want it to be, mostly because I don’t want the idea to be altered by distraction. That process can take weeks or months. There’s something a bit obsessive and singular about that, so I think it naturally results in my work having a sense of stillness.

Q6. Alongside painting, you create limited run linocut prints. What does work in this medium offer that feels different from oils and gouache?

I think there’s something very soothing in the tactile and repetitive carving process. There are a reduction and simplicity needed in making the linocuts that offsets the complexity of my paintings. This is good for my practice in that it helps me practice seeing the bigger picture in my ideas. In some ways it’s also a good balance and half-way point between my work as graphic designer, in its linearity and limited colour usage, but also in the freedom it offers to make anything as an artist. I’ve not made any new linocuts for a while and I’m currently planning a twelve-block series. I’m looking forward to seeing it progress.

Wrapping our conversation with Jennifer, I couldn’t stop thinking about something she said that for 18 years, she had everything except the one thing that mattered.

She had built a career as a graphic designer. Financial stability, professional respect, a life that looked successful from every angle. But she wasn’t creatively fulfilled. And here’s what got me: she didn’t apologize for that emptiness. She didn’t minimize it or convince herself she should be grateful for what she had. She just admitted the truth, that security doesn’t equal satisfaction. That you can do everything society tells you is right and still wake up feeling like you’re living someone else’s life. Most of us spend decades pretending that’s enough. Jennifer stopped pretending.

What really stayed with me is how she turned her darkest period into her biggest transformation. She didn’t run from that darkness or intellectualize it. She recognized it as a mirror showing her what she couldn’t yet say out loud: she was struggling with depression and anxiety. So, she got help. She did the hard, unglamorous work of healing. And when her art changed, it wasn’t because she decided to paint “happier” things it was because she had genuinely transformed. Now her work doesn’t ask you to witness her pain. It offers you space to explore your own inner world. That shift, from making art about yourself to making art that holds space for others, is everything.

There’s also something quietly powerful in how she protects what matters. She sits with ideas for months before touching a canvas. She doesn’t let outside voices rush her or dilute her vision. She waits until she knows exactly what she’s trying to say. In a world that rewards speed and constant output, that kind of patience feels revolutionary. She’s not chasing trends or trying to keep up. She’s building something that lasts.

And here’s the truth that cuts through everything else: Jennifer proved that you don’t have to choose between beauty and depth. Her work is soft, delicate, filled with flowers and light and it’s also profound. She understands that beauty isn’t shallow or decorative. It’s how we connect. It’s how experience becomes something we can share. She uses symbolism not to confuse people but to create space for them to bring their own meaning, their own story, their own need. That generosity trusting your audience enough to let them complete the work in their own way is what turns art into conversation instead of monologue.

If there’s anything I’m taking from Jennifer’s story, it’s this: fulfilment isn’t something you stumble into. It’s something you choose, even when that choice looks reckless to everyone else. She walked away from stability because she knew staying would cost her something more valuable than security. And that courage to bet on yourself when you have everything to lose that’s what keeps any creative practice alive. That’s what makes art matter. That’s what makes life worth living.

Follow Jennifer from the links below to witness how she transforms flowers, smoke, and symbolism into paintings that invite you to bring your own story.