This Is for Anyone Who Thinks Taking Time Away from Art Means Falling Behind I Elizabeth Bessant

At Women in Arts Network, we’ve spent enough time curating to know that the most compelling work rarely announces itself. It doesn’t walk in demanding attention. It just sits there quietly, holding more than it shows, waiting for you to slow down and actually look.

For our Birds exhibition, we wanted artists who understood birds as something beyond beautiful subjects. Not just feathers and flight rendered skillfully on canvas. But presence. The quiet kind that lives in the corners of our homes and our memories without us ever consciously inviting it in. The kind we stop seeing precisely because it’s always been there.

While reviewing submissions, Elizabeth Bessant’s work caught us in a way we didn’t expect. There was something in it that felt earned. Not just technically accomplished but lived. Like someone who had gathered things quietly over a long time and finally found the right surface to put them all together.

We selected Elizabeth because her work carries a kind of honesty that only comes from having truly lived outside of art and then choosing to return to it anyway. And anyone who has ever stepped away from something they loved and found the courage to come back knows that the return is never simple. It takes something. A willingness to start again. To face what you left and trust that you still have something to say.

Before we hear from Elizabeth directly, here’s what you should know about her.

She had a real breakthrough early in her career. Work accepted into the Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. Genuine attention from the London art market. Things were building in a direction that felt significant. And then life, as it does, asked something different of her. She stepped away from fine art for 28 years to raise her son and work in couture fashion design.

28 years is a long time. Long enough for most people to assume the chapter is closed.

But Elizabeth never really left. The way she thought about surface, layering, structure, the instinct to build things carefully and with intention, all of that continued in a different form. She dyed her own fabrics. She translated her printmaking vocabulary into beaded surfaces. The art was still happening. It had just found a different container.

When she eventually returned to fine art, she didn’t come back to where she started. She came back with everything those 28 years had given her. And that changes the work completely. You can feel it. The depth that only accumulates when you’ve lived fully and brought all of it with you.

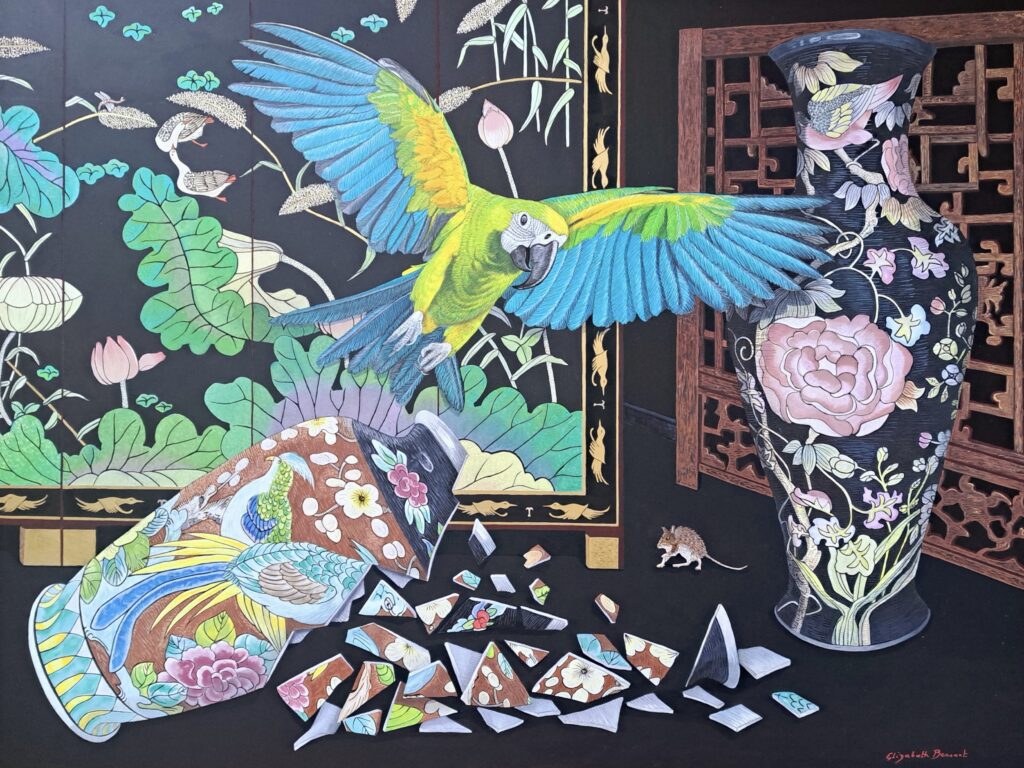

Her birds are where this becomes most visible and most moving. She’s noticed something that most of us have stopped noticing entirely. Birds are everywhere in our domestic spaces. Wallpaper, ceramics, textiles, the corner of a painting we pass every morning. They’ve become so familiar we look right through them. Tiny witnesses to our daily lives that we’ve trained ourselves not to see anymore.

Elizabeth wants to restore that visibility. Not by painting birds as they scientifically appear, but by asking what they carry. What hides inside something so familiar. How a small decorative motif can hold suggestions of freedom, of longing, of absence, of home, all at once, quietly, without ever demanding you notice.

There’s something deeply generous about that kind of attention. Looking closely at what everyone else has learned to overlook and saying, this still matters. This deserves to be seen.

Now let’s hear from Elizabeth about what those 28 years away actually gave her, why she keeps returning to birds as a subject, and what it really means to come back to something you love after a long time away.

Q1. Could you share how your training in silkscreen printmaking and decades in couture influenced the visual language you returned to when you came back to fine art?

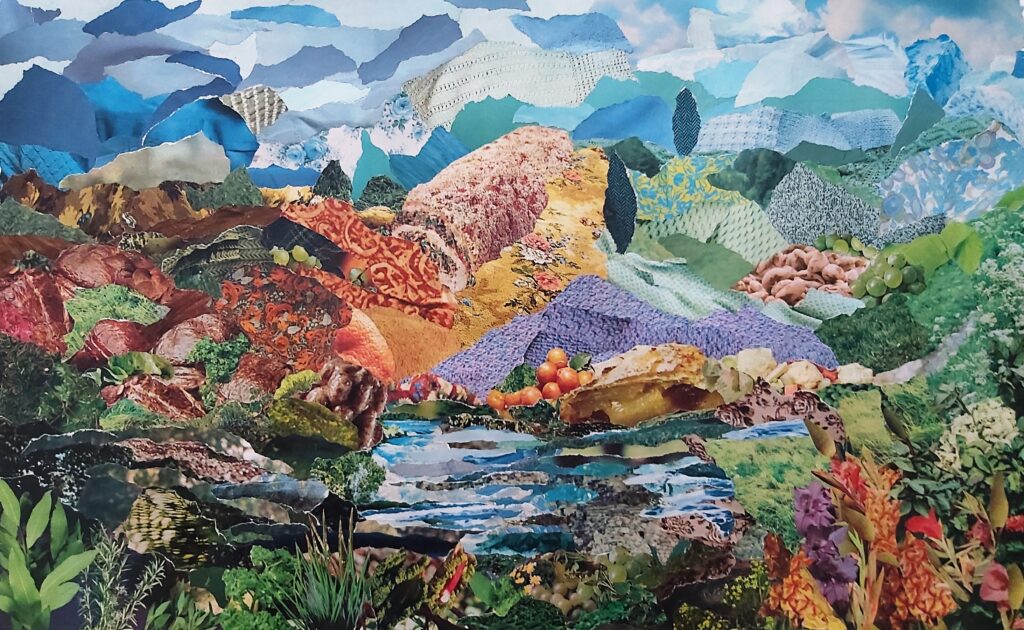

I trained as a silkscreen printmaker and began my career in 1982 when one of my prints was accepted into The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. At that time, silkscreen printmaking was not widely recognised as fine art, so this marked a significant breakthrough and brought early attention from the press and the London art market. After 28 years, I moved into couture fashion design partly in search of a change and partly because it was a more manageable practice while raising my son. Much of the work could be done from home, particularly in the early years. My background in printmaking strongly influenced the designs: I dyed and created many of my own fabrics and translated the dot structures of my prints into beaded surfaces. Coming from an art rather than a fashion background proved central to the originality and success of the work. When COVID brought the industry to a halt, it created space for reflection. Couture was always intended as a mid-career chapter, and I returned to art when the time felt right. In my early work, these earlier practices converge through layered paper collages that echo the layering of inks in silkscreen, the construction of fabrics and appliqué in couture, and the use of thousands of crystals as a visual thread linking my past and present. My latest work continues this exploration of layering, but now through paint and assorted pens, often worked over 24k gold leaf. These surfaces bring together my printmaking and couture histories in a more distilled, painterly form.

Q2. Your work oscillates between intimate portraits, pop-culture references, and vast hybrid terrains. What principles guide you when moving between these different subject matters?

My work moves between portraits, pop culture, imagined landscapes and birds but I approach them all in a similar way. I start from a place of closeness – I want the viewer to feel something personal or familiar. I use pop culture because it’s part of everyday life. These images and references shape how we see ourselves, often without us noticing, and I’m interested in how they mix with private thoughts and emotions. The hybrid spaces come from how I experience the world: memories, media and imagination overlap rather than exist separately. Letting these things sit together creates space for the viewer to form their own connections.

Q3. Several of your bird and pop art pieces play with iconography and consumer imagery. How do you see the relationship between popular culture and art historical reference in your work?

I see pop culture and art history as part of the same visual language. Both use symbols and images that carry meaning because we’ve seen them many times. When I use consumer imagery or pop references, I’m interested in how they connect to older art – how both can show ideas about power, desire, or belief. A cartoon or ad image can feel like a modern myth, just like classical or religious art once did. Putting pop culture and art-historical reference together lets them talk to each other, showing how images shape the way we see the world. I don’t see pop culture as separate or less serious, it’s part of the same shared visual memory that art history comes from.

Q4. You’ve been a Fellow of the Royal Society of Artists and exhibited internationally; how have these institutional contexts influenced the evolution of your work over the last decade?

Being part of institutions like The Royal Society of Artists and showing my work internationally has shaped my practice in subtle but important ways. On one level, it offers validation and visibility – being in dialogue with other artists, curators, and audiences pushes me to think more critically about my choices. Being part of these institutions and showing work around the world has exposed me to different cultures, ideas, and ways of looking at art. It makes me think about how people from different backgrounds read my work, and encourages me to make pieces that feel personal but also open to many interpretations.

Q5. You once said that artists question and influence how people perceive the world. How do you see your collages as offering new ways of seeing beyond surface recognition?

For me, collages are a way of shifting perspective. By cutting, layering, and reassembling images, I can take familiar things – faces, objects, landscapes, pop culture icons – and place them in unexpected relationships. That break from the unexpected forces the viewer to look more closely, to slow down, and to reconsider what they know. I’m interested in what lies beneath surface recognition – the emotions, contradictions, and histories that a single image might carry but that we often overlook. In my work, a bird next to a celebrity face, or a fragment of a landscape, isn’t just playful – it’s a way of opening a small space where perception can shift, and where ordinary things can feel strange, intimate, or even uncanny.

Q6. What themes or visual questions are you currently returning to in your studio and what feels unfinished or open in your practice?

Lately, I keep coming back to birds and their presence in our domestic and visual lives. They appear in wallpaper, ceramics, textiles, even advertising – tiny witnesses to our everyday spaces. I’m fascinated by how these motifs carry both comfort and symbolism: they’re decorative, familiar, but also capable of hinting at freedom, longing, or even absence. What feels open in my work is exploring how these birds connect in memory, culture, and imagination. I’m not trying to show them exactly as they are, but to look at how they live in our homes, in our minds, and in history.

Q7. How do you think about the relationship between cut edges, torn paper, and handmade mark-making in your work are they discordant, harmonious, or both?

For me, cut edges, torn paper, and handmade marks all bring different energies to a piece. A cut is precise, a tear is instinctive, and a mark is a trace of my hand. I don’t see them as fully harmonious or discordant – they exist in a kind of tension. That tension is what gives the work energy. The sharpness of a cut against the irregularity of a tear, or the texture of marks, makes the work feel both controlled and spontaneous. These elements also show the viewer the process of making – the work is touched, handled, and thought through, not just a finished image. The mix of control and chance mirrors how we experience the world: orderly, messy, and always shifting.

Q8. When viewers respond to your work whether drawn to detail, humour, or cultural reference how do their interpretations align with what you were thinking while making it?

I see viewers’ responses as a kind of conversation with the work. Often, people notice details, humour, or cultural references that I didn’t even consciously plan – they bring their own experiences and associations, and that can open the work in unexpected ways. At the same time, many responses do match what I was thinking. People notice the tension between intimacy and spectacle, the mix of memory and culture, and the small details that carry emotion. I don’t try to control how people see the work, but I hope it sparks curiosity and that they sense some of the ideas or feelings I was exploring.

Q9. What advice would you give to artists who are drawn to collage and mixed media but struggle to find a personal voice rather than inherited imagery?

I would say the first step is to trust your own instincts and experiences. Collage, mixed media, and other materials carry a history, but your personal voice comes from how you respond to them, not just what has been done before. Spend time experimenting and playing – layering, erasing, or combining materials in ways that feel natural to you. Let accidents and surprises guide you as much as intention. Also, look closely at the world around you – your memories, your home, your environment – and let that inform your work. Even small, personal details can become powerful imagery when you make them your own. Over time, the repeated gestures, choices, and marks you make will start to form a distinct language that is unmistakably yours. Finally, be patient. Finding a personal voice isn’t about rejecting influences; it is about absorbing, responding, and transforming them until the work feels alive and authentic.

As we wrapped our conversation with Elizabeth, I found myself thinking about something she said almost casually, like it wasn’t a big deal. She stepped away from fine art for 28 years. Just said it simply, without drama or apology.

And I couldn’t stop thinking about what those 28 years actually looked like. She wasn’t sitting around waiting to come back to art. She was raising her son. Building a couture career from scratch. Dyeing her own fabrics by hand. Taking everything she knew about printmaking and figuring out how to translate it into beaded surfaces. She was completely, fully in it.

So when she came back to fine art, she didn’t walk in empty handed. She walked in with 28 years of building things, layering things, solving problems with her hands. And you can see it in her work. The way surfaces accumulate. The way different materials sit together without fighting. The way her printmaking history and her couture history and her fine art present all exist in the same piece like they were always meant to.

The bird thing specifically is what I keep coming back to. She noticed something that’s so obvious once you hear it but that none of us had really thought about. Birds don’t just live outside. They live in our homes. In the wallpaper we stop seeing after the first week. In the ceramics we use every morning without looking at them. In textiles we’ve owned for years. They’re everywhere and we walk past them every single day without actually registering they’re there.

And Elizabeth looked at that and thought, what are they carrying? What does a bird on wallpaper say about freedom when it’s painted onto something that can’t move? What does a bird on a teacup hold in terms of longing or comfort or memory? She turned something we’d all stopped seeing into a genuine question worth asking.

That’s what 28 years of living fully outside your original practice gives you. A different way of noticing. A patience with the overlooked. An eye for what’s sitting quietly in plain sight waiting for someone to actually look.

If you’re an artist who has taken time away, or is thinking about it, or is in the middle of a chapter that doesn’t look like art but feels connected to it somehow, Elizabeth’s story is genuinely reassuring. Not in a vague motivational way. In a specific, practical way. The skills you’re building right now, whatever they are, will find their way back into your work. The time you’re spending living fully outside the studio is accumulating into something. You won’t see it yet. But it’s there. And when you return, you’ll bring it all with you without even trying.

Follow Elizabeth from the links below to see work that holds multiple lives in a single surface, birds that have been sitting in your home this whole time waiting to be noticed, and proof that 28 years away from art can give you more than 28 years of never stopping.